Analysis of Strategies for Translating Toponyms in The Headless Horseman (based on Mayne Reid’s Novel and Its Translation into Kyrgyz)

Analysis of Strategies for Translating Toponyms in The Headless Horseman (based on Mayne Reid’s Novel and Its Translation into Kyrgyz)

Abstract

This study examines strategies for rendering toponyms from English into Kyrgyz via Russian, using Mayne Reid’s novel The Headless Horseman as a case study. Focusing on maintaining the novel’s cultural nuance and semantic accuracy, it compares specific place-names in the English source text with their Russian and Kyrgyz renditions. The analysis demonstrates how extralinguistic factors like cultural, socio-political, and economic influence translator’s choices and reveals the predominant techniques (transliteration, calquing, descriptive rendering, etc.) that help to preserve the local colour of the source text. The research also highlights the challenges of carrying thematic, historical, and linguistic elements across languages. Conclusions assess the nature of toponymic transfer in indirect translation and evaluate how translator’s decisions align with established principles for rendering toponyms. This work contributes to onomastics and translation studies by offering practical recommendations for translators aiming to achieve both linguistic precision and cultural resonance in cross-cultural literary contexts.

1. Introduction

Translating the literary works demand special care in rendering proper names, especially toponyms, because they carry important cultural and geographical information. In many cases, foreign place names have no direct equivalents in the target language and fall into the category of non-equivalent lexis. Translation theory broadly holds that proper names (toponyms, anthroponyms, etc.) are not “translated” but are transferred into the target language through various translation strategies. In practice, translators most often use transliteration or transcription techniques to preserve the original form, since substituting or explaining the name can render the text more accessible but risks losing its authenticity.

Toponyms are the important part of the society’s linguistic heritage, that carry cultural, historical, and political significance that may be distorted during the translation process. The Headless Horseman (1865) demonstrates this challenge and its 19th-century Texan setting demonstrate myriad river, geographical names and towns that are completely unfamiliar to Kyrgyz and Russian readers. Rendering these names into the Kyrgyz and Russian languages requires balancing phonetic fidelity and linguistic precision to reach the text’s integrity.

The authors of this paper have investigated the difficulties of toponymic translation, how extralinguistic factors such as socio-political contexts can influence linguistic choices. The present paper applied established theoretical frameworks

, , , to evaluate whether English place-names retain their meaning when mediated first through Russian, then into Kyrgyz.Geographical names including cities, landmarks, and regions present significant challenges for cross-cultural communication because of their layered connotations

. Also, the differences in phonetics, morphology, and cultural context bring some complications to the task , . So, it is necessary for translators to choose between:- Direct rendering (transliteration / transcription) of toponyms using the target language’s script or sound systems.

- Semantic rendering (including translation or explanation) related to conveying the main meaning of toponyms, providing explanations or descriptions.

By examining the English source text alongside the 1959 Russian and Kyrgyz versions of The Headless Horseman, this study identifies the strategies employed most notably transliteration by both Russian and Kyrgyz translators, and assesses their effectiveness. The first goal was to classify the translation techniques applied to toponyms. Then to analyze illustrative examples and discuss the translators’ rationales and the impact on reader perception. The methodology combines comparative-contrastive analysis, descriptive commentary, and quantitative tallying of strategy frequencies, grounded in theories of non-equivalent lexis and proper-name translation.

Contemporary researches confirm these observations. For example, D. A. Smirnova and A. Kh. Abdulmanova, analyze name-translation strategies in English fairy-tale literature rendered into Russian and demonstrate the predominance of transcription and transliteration for both anthroponyms and toponyms

.This article examines the translation strategies used to translate toponyms from English into Kyrgyz, based on Mayne Reid’s The Headless Horseman: A Strange Tale of Texas (1866) as its primary source. Rich in American Southern realia including names of rivers, forts, and settlements, Reid’s novel was first rendered into Russian, then in 1959 into Kyrgyz by S. Bektursunov

. Since the Kyrgyz version relies on the Russian intermediary, it offers a clear example of mid-20th-century Soviet translation practices for foreign place-names.The main objectives of the paper were to:

- Provide classification of the types of translation techniques applied to toponyms in the Kyrgyz text influenced by Russian.

- Choose and analyze representative examples of toponyms and their translations.

- Discuss the translators’ choice of particular translation strategies that make a great impact on the reader’s comprehension.

Our corpus consists of Reid’s original English novel and its Kyrgyz translation . Methodologically, we combine a comparative-contrastive analysis with descriptive commentary and quantitative counting of strategy frequencies. The theoretical framework draws on studies of non-equivalent lexis and proper-name translation , , and on recent empirical research into translation practice .

2. Theoretical Framework

Translating toponyms falls under onomastics, the study of proper names, and presents unique challenges. A toponym usually has no independent semantic content outside its source language, though it may contain a transparent meaning (e.g., Rio Grande that literally mean “Big River” or Casa del Corvo in Catalan/Spanish have a meaning “House of the Crow”). In some cases, a toponym is an unmotivated name (e.g., Texas — the name of a state, not translatable), while in others, it can be partially descriptive. So, the translation strategies may vary accordingly.

Classical translation theory identifies five principal methods for toponym transfer

, : Transcription: Reproducing toponyms in the source language through the target language’s phonetic system (e.g., English Texas, "Техас" in Cyrillic); Transliteration: Providing each source‐language letter to its closest target‐language equivalent, and it often overlaps with transcription to maintain both form and pronunciation in practice; Calque translation: Rendering each element of a semantically transparent name word-for-word (e.g., Rio Grande — "Улуу дарыя" — “Big River”); Descriptive translation: Replacing the original toponym with an explanatory phrase either inline or as a footnote when the name’s meaning is important but obscure (e.g., Llano Estacado — "Льяно Эстакадо талаасы" — Степь Льяно Эстакадо);Functional analogue: Substituting the foreign name with a familiar local equivalent, that is extremely rare for real places due to the risk of misrepresenting factual information.

Transcription and transliteration best preserve a work’s authenticity of place-names by adapting only script and pronunciation. Calques or descriptive renditions should be reserved for instances where a toponym’s semantic content is vital yet not self-evident to the target reader. Vlahov and Florin

classify toponyms as “realia” requiring special attention: depending on context, the translator either transcribes them or explains them as needed for comprehension. However, in most cases, toponyms are factual realia — conveying place-name information rather than symbolic meaning and thus are best neutrally transferred without translating their meaning.Beyond linguistic considerations, established translation norms in the target language usually influence the choice of the translation strategies. For example, Russian maintains standardized exonyms exist for most country es and major geographical features (e.g., London — Лондон, New York — Нью-Йорк). Similarly, Kyrgyz, using a Cyrillic orthography inherited from Soviet practice, often adopts Russian transliterations for international place-names. Mid-20th-century Kyrgyz translation guidelines thus advised preserving foreign names unchanged, except when well-known translated exonyms existed or when explanatory additions were necessary for the plot

.Guided by these principles, the following sections analyze how toponyms in The Headless Horseman were rendered into Kyrgyz, the influence of Russian mediation, and the strategies ultimately adopted.

3. Methodology and methods

This study employs a mixed-methods approach that integrates qualitative and quantitative analyses to provide a holistic understanding of toponym translation in The Headless Horseman into Kyrgyz via Russian. In the application of the qualitative approach, all the toponyms translated into the Kyrgyz language were examined side by side with its English original and the Russian intermediary to uncover the translator’s choice considering cultural, linguistic, and contextual nuances. This close reading show how extralinguistic factors such as Soviet-era principles and linguistic conventions shaped those decisions of a translator. During the quantitative analysis, the entire corpus is systematically divided into five key strategies — transliteration, transcription, calque, descriptive translation, and functional analogue and their frequencies in both the source text (ST) and the target text (TT) were provided. By combining interpretive insights with measurable data, the study both reveals overall patterns in the translator’s approach and explains individual translation decisions.

4. Analysis

Mayne Reid’s The Headless Horseman abounds with toponyms rooted in its Texan setting and adjoining Mexican borderlands. In the 1866 English original

, place names include Texas, Mexico, Rio Grande, Nueces, Leona, Casa del Corvo, Fort Inge, and others. S. Bektursunov’s 1959 Kyrgyz translation consistently transfers all of these via transcription or transliteration.Nearly every toponym in the Kyrgyz text mirrors its source form in Cyrillic, requiring only minimal phonetic adaptation. For example:

- Texas — Техас (aligning with the established Russian exonym and preserving English pronunciation);

- Mexico — Мексика (identical to Russian and international usage).

Rio Grande — Рио-Гранде and Nueces — Нуэсес, with the generic term “river” ("дарыя") omitted where context suffices but added. For example, Леона дарыясы (“Leona River”) — to satisfy Kyrgyz syntax.

The Spanish estate name Casa del Corvo (“House of the Crow”) appears as Каса дель Корво, identical to its Russian intermediary form rather than calqued into Kyrgyz (e.g., “Корво үйү”). This preserves its exotic resonance; no explanatory footnotes were supplied, in keeping with Soviet-era conventions that favored seamless narrative flow over copious annotation.

Fort Inge likewise follows the foreignizing pattern. In the absence of a direct quotation from Bektursunov

, all available evidence indicates it appears as Форт Индж or, when the generic term is rendered, Индж чеби (“Inge Fortress”). This treatment of proper name in transcription plus Kyrgyz generic term is entirely in line with the overall approach: foreign place names are carried over unchanged, with generic nouns translated only as needed for grammatical clarity.Among the major part of toponyms, this uniform translation strategies as pure transcription/transliteration prevails. Here we couldn't notice any semantic calques, any substitutions, or omissions: every toponym in Reid’s text is faithfully preserved. This homogeneity demonstrates the translator’s commitment to maintain the novel’s geographical texture.

When mapping English phonemes into Kyrgyz Cyrillic, standard Russian-style conventions guide choices: x — “х” (e.g., Техас); j — “дж” (e.g., Индж; note that native Kyrgyz norms might instead render this as “Инж”).

Letters Ll (as in Llano) generally becomes “ль” or “й,” though detailed treatment of that specific toponym is not directly attested in Bektursunov’s edition.

As a result, the target text in Kyrgyz is peppered with foreign names that may seem unusual to monolingual readers. However, bilingual audiences (speak both in Kyrgyz and Russian) readily recognize standard forms like “Техас” and “Мексика.” In grammatical point of view, these names fully integrated into Kyrgyz through regular case and possessive suffixes Техаста (“in Texas”), Мексикадан (“from Mexico”) showing their full assimilation into the target-language text.

In sum, the dominant strategy is foreignization via transliteration. By eschewing adaptations, explanations, or local analogues, the translation achieves high formal accuracy in rendering place-name realia, even though semantic nuances (e.g., Nueces meaning “nut trees”) remain opaque to the Kyrgyz reader, a detail deemed non‐essential for narrative comprehension.

This study applies onomastic classification

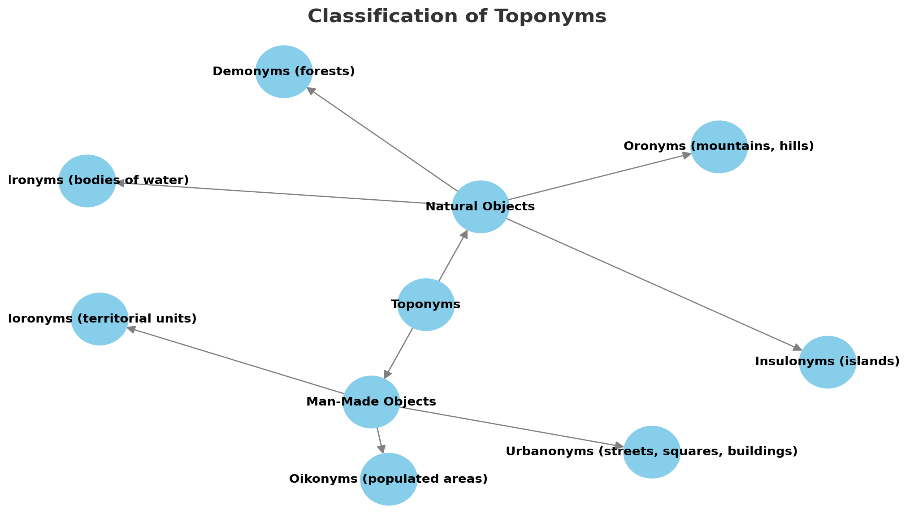

and name-translation paradigms to systematically categorize these toponyms and assess the effectiveness of transcription, transliteration, and adaptation strategies in preserving the novel’s cultural essence. Place names function not merely as locators but as markers of identity and collective memory , , dynamically interfacing with sociocultural, historical, and geographical layers .- Natural Objects: Hydronyms (bodies of water), oronyms (mountains, hills), demonyms (forests), insulonyms (islands).

Figure 1 - Classification of toponyms by natural vs man-made categories

Table 1 - Translation of Natural-Object Toponyms in The Headless Horseman

Category | Source Text (ST) Excerpt | Target Text (TT) Excerpt | Explanation |

Hydronyms | “…landed at Indianola, on the Gulf of Matagorda…” (p. 3) | "Индианолго, Матагорд булуңунун жээгине…" | Gulf of Matagorda is rendered unchanged; "булуңунун жээгине" (“to the shore of the bay”) provides context. |

Oronyms | “…the ci-devant stable-boy of Castle Ballagh…” (p. 30) | "…Баллинаслой ярмаркасында…" | Castle Ballagh is transliterated without semantic explanation, maintaining its historical authenticity. |

Insulonyms | “Ichabod held the reins tightly…” (p. 44) (metaphorical “reins”) | "…тизгинди бекем кармады…" | The literal reins are preserved, and the phrase integrates naturally into Kyrgyz idiomatic usage. |

So Hydronyms such as Gulf of Matagorda remain formally unchanged, with only Kyrgyz case marking (-дун жээгине) added for grammatical coherence.

Oronyms like Castle Ballagh receive a straight phonetic rendering, preserving their historical and cultural colours.

Symbolic terms (e.g., “reins” as control imagery) are adapted into relevant Kyrgyz idioms that show flexibility when the term carries thematic weight rather than locational reference.

By avoiding semantic substitutions or explanatory notes, the translator maintains high formal accuracy and the exotic flavor of the source text. At the same time, minimal descriptive additions meet Kyrgyz syntactic requirements without diluting the source’s geographic authenticity.

According to the contemporary translation theory , , the approach for proper names are really supported and emphasize that literal renderings preserve foreign color while selective adaptation addresses reader comprehension. Research on toponyms in English and their translations into Kyrgyz influenced by Russian , further confirm that the transcription technique can be coupled with cultural adaptation for the best balancing linguistic fidelity with intelligibility.

5. Findings and Results

The analysis reveals that S. Bektursunov consistently adopted a minimal-intervention approach to toponyms, fully in line with mid-20th-century Soviet translation norms that prioritized preserving the foreign “color” of proper names over cultural domestication. By opting almost exclusively for transliteration/transcription, the translator maintains the sense of “otherness” integral to Reid’s Texan and Mexican settings, what Venuti (1995) calls a foreignizing strategy, while leaving the local color of the American frontier intact.

It is important to note that the domestication strategies including the semantic substitution, explanatory glosses, or functional analogues do not exist. These examples match with Soviet-era practice influenced by Russian intermediary texts. So Bektursunov followed the established Russian forms (e.g., "Техас", "Мексика", "Рио-Гранде"), rendering them unchanged in Kyrgyz. This type of indirect, two-step translations (English — Russian — Kyrgyz) are connected with the historical influence of Russian on Kyrgyz exonymy.

The advantages of the mentioned single-strategy approach include:

- Sustainability across major part of toponyms, helping bilingual readers who wish to cross-reference ST and TT.

- Formal accuracy, preserving original orthographies and phonetics.

- Matching with the literary genres: For instance, adventure fiction benefits from the exotic ambiance of untranslated place-names.

The drawback lies in potential comprehension gaps. Readers can be unfamiliar with the source text or languages receive no semantic cues (e.g., ‘Nueces’ meaning “nut trees”) and remains opaque. Consequently, according to the Soviet guidelines of that period discouraged overloading literary editions with footnotes or commentary, favoring aesthetic unity over factual explanation. In contrast, contemporary translators in the era of globalization might selectively introduce explanatory notes or maintain original forms, depending on target-audience needs.

Overall, Bektursunov’s practice clearly matches with classical translation theory related to the proper names that are rendered rather than translated

, . Even semantically transparent toponyms escape calque, reflecting Komissarov’s assertion that, in adventure fiction, realism (i.e., faithful reproduction of foreign place-names) outweighs the need to explicate onomastic meanings .Hydronyms (e.g., “Leona River” — "Леона суусу", “Rio de Nueces” — "Нуэсес дарыясы") predominantly appear in transliterated form with occasional generic Kyrgyz descriptors (суусу, дарыясы) added for clarity.

Man-made names (e.g., “Casa del Corvo,” “Fort Inge,” “San Antonio”) show selective adaptation: “Casa del Corvo” sometimes becomes "Корво үйү" (localizing ‘house’) whereas “Fort Inge” appears as "Инж форт" (transliteration + generic term in Kyrgyz word order).

Such nuanced application highlights that even within a broadly foreignizing stance, the translator may apply minimal cultural adaptation when it improves target-reader comprehension without sacrificing formal fidelity.

Table 2 - Translation Strategies for Geographical and Cultural Elements in The Headless Horseman

Translation Strategies | Example (ST) | Translation (TT) | Explanation |

Literal Translation | “Ichabod rode home through the woods.” | “Икабод токой аркылуу үйүнө кайтып бара жатканда...” | Preserves the original meaning and sentence structure, ensuring clarity and accuracy. |

Transliteration | “Sleepy Hollow” | “Слиппи Холлоу” | Direct transliteration retains the cultural and geographical identity of the place. |

Cultural Substitution | “Ichabod enjoyed a hearty breakfast of pancakes.” | “Икабод нан жана каймактан даярдалган эртең мененки тамакты жактырчу.” | Substitutes “bread and cream” for pancakes to adapt to Kyrgyz food culture while retaining meal context. |

Paraphrasing | “The schoolhouse was a low building of one large room.” | “Мектеп — чоң бир бөлмөлүү төмөнкү имарат болчу.” | Simplifies and rephrases the description to fit natural Kyrgyz sentence structure while retaining meaning. |

Addition | “Ichabod rode home through the woods.” | “Ичабод токой аркылуу үйүнө кайтып бара жатканда, караңгы жана коркунучтуу болгон.” | Adds descriptive details (“dark and scary”) to enhance the atmosphere for Kyrgyz-speaking readers. |

Omission | “He was tall, but exceedingly lank, with narrow shoulders, long arms and legs.” | “Ал узун бойлуу жана арык эле.” | Omits minor details to streamline reading for the target audience. |

Cultural factors significantly determine whether a toponym is transliterated or adapted. For instance, references to Texan customs or historical contexts may be minimized if considered irrelevant to Kyrgyz audiences. Translators weigh extralinguistic elements such as local familiarity and socio-historical resonance when deciding to adapt, substitute, or retain the original name structure.

Natural objects (hydronyms, oronyms) and man-made objects (forts, towns) are present at nearly equal frequencies in the selected corpus.

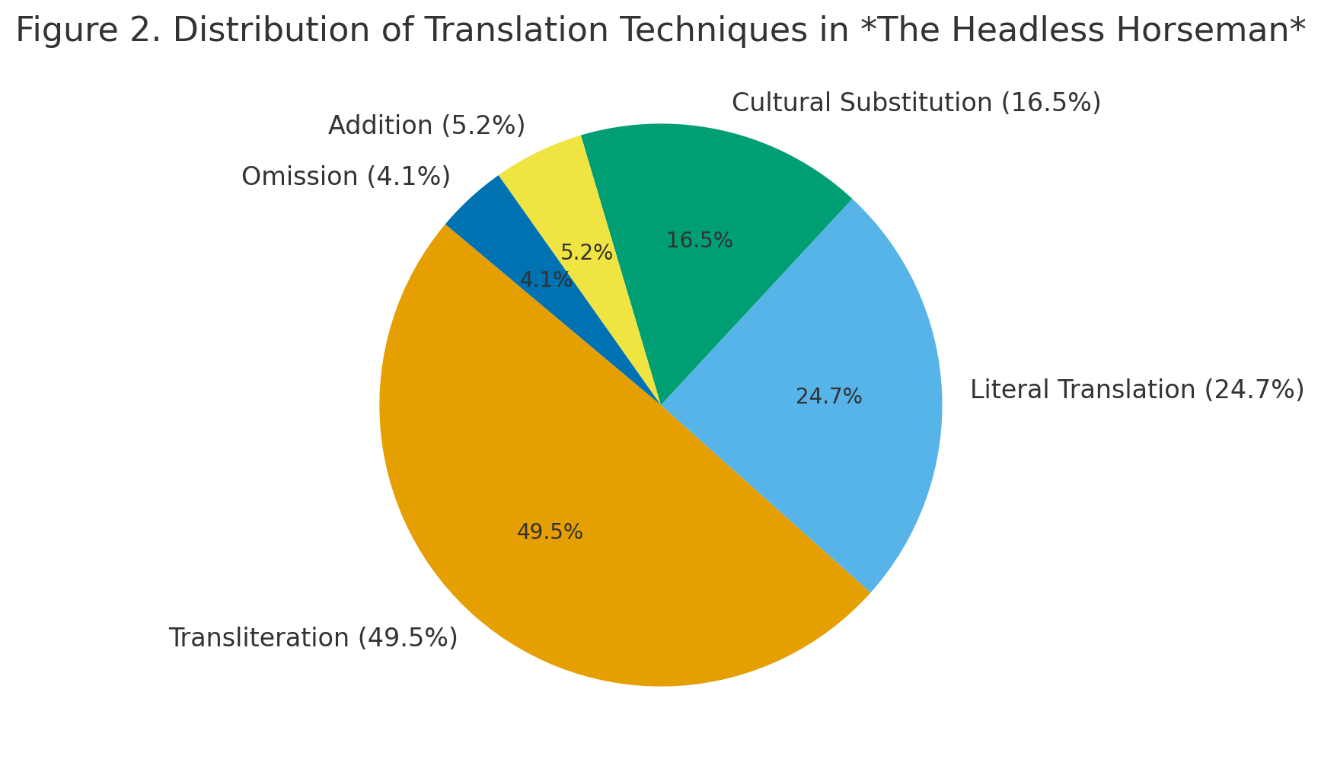

A quantitative overview confirms the predominance of transliteration (49,5%) and literal translation (24,7%), with cultural substitutions, additions, and omissions making up the remainder. Despite its minority status, cultural substitution plays a vital role in conveying semantic nuance where pure transliteration might leave readers disoriented:

- Transliteration (49,5%): Common for proper nouns and unique place names (e.g., "Sleepy Hollow" — "Слиппи Холлоу").

- Literal Translation (24,7%): Used for straightforward, descriptive names (e.g., "Gulf of Matagorda" — "Матагорд булуӊунун жээги").

- Cultural Substitution (16,5%): Employed to make culturally specific references relatable to Kyrgyz readers (e.g., substituting “pancakes” with “bread and cream”).

- Addition (5,2%): Provides context or enhances the atmosphere (e.g., adding “dark and scary” to describe the forest).

Figure 2 - Distribution of Translation Techniques in The Headless Horseman

6. Conclusion

The translation of Mayne Reid’s The Headless Horseman into Kyrgyz shows a clear preference for foreignization, combining phonetic authenticity with enough cultural intelligibility to preserve the novel’s exotic ambiance. By transferring all types of toponyms directly into Kyrgyz with minimal phonetic adaptation, the translator upheld mid-20th-century norms that favor transcription over translation of onomastics. This strategy maintains both geographic authenticity and the adventure genre’s aesthetic appeal: readers experience distant Texas and Mexico almost as if in the original, without the text being “domesticated”.

Our cluster-based classification dividing toponyms into natural (hydronyms, oronyms, insulonyms) and man-made (oikonyms, horonyms, urbanonyms) categories reveals that while transliteration and literal transfer dominate across the board, selective cultural adaptations (e.g., adding generic Kyrgyz descriptors or occasional lexical additions) support reader comprehension when necessary. These choices clearly reflect not only theoretical guidelines for toponyms transfer

, but also extralinguistic factors, such as Soviet-era reliance on the period when the Russian intermediaries and prevailing socio-political attitudes toward foreignness.In conclusion, it is important to note that mid-20th-century Kyrgyz editions of foreign adventure fiction prioritized fidelity to the source text’s toponymic system, foregoing explanatory glosses in favor of preserving original forms. Our findings not only enrich comparative onomastic research across former Soviet languages but also offer practical guidance for today’s translators: the decision to retain or explain a place-name should be informed by the work’s genre, its intended purpose, and reader expectations. In contexts where preserving “local color” is paramount such as literary adventure, foreignization remains an effective strategy.