Сравнительное исследование онлайн-обучения в Монголии и Японии: размышления на основе опыта пандемии COVID-19

Сравнительное исследование онлайн-обучения в Монголии и Японии: размышления на основе опыта пандемии COVID-19

Аннотация

Пандемия COVID-19 вызвала резкий глобальный переход от традиционного очного образования к онлайн-обучению, что создало особые трудности для преподавания японского языка в Монголии. Данное исследование анализирует структурные и педагогические сложности, возникшие в ходе этого перехода, и рассматривает эффективные образовательные практики японских учебных заведений, включая гибридные и смешанные модели обучения. На основе сравнительного опроса преподавателей из 10 образовательных учреждений в Монголии и 10 образовательных учреждений в Японии, преподающих японский язык, изучаются различия и сходства в подходах к организации онлайн-обучения. Несмотря на возросшую популярность дистанционного формата в Монголии, многие учреждения продолжили использовать традиционные методы обучения без соответствующей адаптации к онлайн-формату. Напротив, японские учебные заведения применяли более гибкие подходы, интегрируя онлайн- и оффлайн-форматы для поддержания высокого качества обучения. На основе полученных данных авторы предлагают стратегии по совершенствованию организации онлайн-занятий в Монголии с акцентом на автономность обучающихся, эффективность преподавания, интерактивность и качество цифрового контента. Результаты исследования направлены на развитие адаптивных и устойчивых моделей дистанционного обучения японскому языку как в Монголии, так и за её пределами.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which emerged in 2019, had a profound impact on education systems around the world. Mongolia, the authors’ home country, was similarly affected; from February 2020, distance education was implemented across all educational institutions nationwide for approximately two years. During this time, although most educators had little to no prior experience with remote instruction, they engaged in extensive trial and error to deliver online classes, thereby gradually enhancing their practical abilities and knowledge in distance education. However, studies examining the processes and challenges faced during this period are scarce. In particular, in the field of foreign language education, where the authors specialize, there was insufficient exchange of information regarding the improvement of distance learning. As a result, institutions returned to in-person classes in 2022 without fully addressing the issues that had arisen. Due to the association of online education with negative academic outcomes, such as declining student performance, there remains a widespread perception that remote instruction was ineffective. The authors began to question whether there is a need to investigate the root causes of this negative perception. Moreover, even in the post-pandemic era, demand for online education has not diminished. Considering that the university to which the authors belong is actively promoting online instruction, the necessity and urgency of this research became evident.

According to the 2021 Survey on Japanese-Language Education Abroad by the Japan Foundation, there are 117 institutions offering Japanese language education in Mongolia (including 23 universities, 29 primary and secondary schools, and 65 language centers), with a total of 13,334 learners and 363 Japanese language teachers . In light of this, the present study seeks to re-examine the compatibility of distance and face-to-face education, explore insights from Japan's experiences, and consider future directions for distance education in Mongolia. Although approximately 80% of these institutions implemented online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, the present survey revealed that currently, only 10 institutions (roughly 10%) are still conducting online classes. This shows that the adoption of online education has significantly declined and remains on a small scale.

2. Background of the Study

Distance education has a history of more than 100 years. Hosaka (2020) classified its evolution into three generations and described modern online education, also known as ICT-based education, as follows:

"With the development of ICT, in addition to print media, mass media, and postal services, computers, the internet, and digital technologies have become integral to distance education. This marks the third generation" . Distance learning formats can be broadly categorized into synchronous learning, where instructors and learners are connected in real time, and asynchronous learning, where they are not. A general term encompassing all combinations of face-to-face and remote instruction is “hybrid learning.” This includes “HyFlex learning,” in which face-to-face and online lessons are conducted simultaneously, and “blended learning,” which integrates prior learning with in-class applications. Classes that allocate time outside the classroom for knowledge acquisition and devote class time to applying and developing that knowledge are classified as “flipped classrooms” . “On-demand learning” refers to uploading course materials to a learning management system (LMS) so students can study at their preferred times.

Regarding the digitalization of education in Mongolia, Ganbat (2022) noted the following: “Over the past 20 years, Mongolia has implemented several national-level projects and programs related to distance education, including the “Mongolian ICT Development Strategy until 2010”, the “National Distance Learning Program” (2002–2010), the “E-Mongolia” program (2005–2012), and the “Higher Education Reform Program” (from 2012 onward), all of which had a certain influence on the education sector .

In 2010, the E-open Institute was established at the Mongolian University of Science and Technology to promote distance education in technical fields. Since 2009, the School of Applied Sciences at the National University of Mongolia has also been conducting distance education using Moodle. In 2023, the School of Arts and Sciences at the same university established a “Hybrid classroom for e-learning”, which is expected to contribute to the further development of online education. While the foundation for distance education has been partially developed across institutions, it cannot yet be said that the necessary environment has been fully established. Although the National University of Mongolia plans to advance digital education, a lack of shared understanding among educators remains a challenge.

3. Literature Review

Globally, research on effective methods and best practices for conducting distance education has been steadily advancing. In Japan, since 2020, the National Institute of Informatics has held 41 symposiums to establish a network for information exchange on online education, during which a total of 357 presentations were delivered. As of October 18, 2024, the CiNii academic database contains 3,844 publications related to distance education, of which 529 are specifically focused on Japanese language education. Furthermore, numerous papers, such as “How did Japanese language teachers respond during the COVID-19 pandemic?” , and books, including “Language Education in the COVID-19 Era” , have been published, reflecting the strong academic interest in online education among Japanese researchers. This section highlights several representative studies in the broader fields of online education, foreign language instruction, and Japanese language education. Russell and Murphy-Judy (2021) recommend the use of the ADDIE (Analyze–Design–Develop–Implement–Evaluate) instructional design model for designing online courses .

The Active Learning Division of the University of Tokyo’s Center for Research and Development of Higher Education (2021) has documented its process of implementing flipped classrooms as a teaching method incorporating active learning. In this initiative, conventional knowledge-transmission-based instruction was redesigned in collaboration with students to foster student-centered learning .

Shibuya (2021) points out that for lessons focused solely on the transmission of knowledge, on-demand video lectures are more appropriate .

Kusanagi and Sakagami (2021) introduced practical examples of enhancing asynchronous foreign language online classes during the pandemic by integrating learning e nvironments and tools, incorporating personalization and gamification elements, and thereby improving learner motivation and participation .

Various ICT-based evaluation systems have also been developed, including a web-based tool to automatically assess writing proficiency based on a corpus of Japanese learners , a diagnostic web test for Japanese grammar comprehension , and a kanji proficiency test .

Furukawa implemented flipped classroom formats for group work, discussions, presentations, and peer evaluations, followed by post-class reflections and self-evaluations using e-portfolios .

Hosaka (2020) emphasized the importance of designing online lessons not by replicating the structure of face-to-face classes, but by creating equally valuable learning experiences through online formats . Hosaka (2021) also presented examples of lesson designs focused on interactive dialogue and conducted wide-ranging studies, including an analysis of the roles of teachers and learners in online Japanese language classes at overseas institutions from the perspective of “presence theory” .

Research in Japan and around the world has steadily advanced in developing effective methods and practices for distance education, particularly in Japanese language instruction, highlighting the importance of instructional design, active learning, and the strategic use of ICT to create engaging and learner-centered online environments.

4. Research Objectives

The primary objective of this study is to clarify the actual conditions and challenges of Japanese language online classes in Mongolia and Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the study focuses on the structure, design, and issues related to Japanese online lessons, and aims to identify both the commonalities and differences between the two countries. Furthermore, the study seeks to draw insights from case studies conducted at Japanese universities and Japanese language schools, examining best practices that can be adopted and adapted for the Mongolian context.

By sharing knowledge and practical experience related to the implementation of online instruction among Japanese language teachers in Mongolia, the study aims to contribute to the future development and enhancement of distance education for Japanese language learning in the country.

5. Methodology

To clarify the actual conditions and challenges of Japanese language online instruction in Mongolia and Japan during the COVID-19 pandemic, a questionnaire survey was conducted targeting Japanese language teachers at educational institutions in both countries. The survey period extended from January 5, 2023, to May 31, 2023, and focused on the period from February 2020 to June 2022, during which distance education was actively implemented.

The survey was administered using a structured questionnaire consisting of 61 items, including both multiple-choice and open-ended questions. The questions were broadly divided into the following three categories:

• Questions 1–7: Items related to Japanese language teachers (e.g., institutional affiliation, teaching experience, subjects taught, duration of online teaching).

• Questions 8–11: Items related to learners (e.g., age, motivation for learning Japanese, Japanese proficiency level, ICT literacy).

• Questions 12–61: Items related to online classes (e.g., class type and subject, digital tools and equipment used, experience with flipped classrooms, advantages and disadvantages, comparisons with face-to-face instruction, lesson structure, classroom activities, challenges in online instruction, and suggestions for improvement).

A total of 20 Japanese language teachers, including 10 from Mongolian institutions and 10 from Japanese institutions, who were responsible for classes focused on foundational Japanese knowledge and the development of the four core skills (listening, speaking, reading, and writing), were invited to participate, and all of them responded. To protect the internal information of the participating institutions, the names of the institutions were anonymized using numerical codes. Care was also taken to ensure that the selected courses and levels from each institution were comparable, in order to minimize discrepancies. Table 1 summarizes the targeted subjects and levels for the survey.

Statistical analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel. Descriptive statistics, including percentage distributions, were calculated to examine the composition of lesson components. Visual representations (graphs) were created to facilitate comparative analysis between Mongolia and Japan.

Table 1 - Survey Subjects and Levels

Subject | Level | Mongolia | Japan |

Japanese Conversation & Listening | Beginner | 1 | 1 |

Pre-intermediate | 1 | 1 | |

Upper-intermediate | 0 | 1 | |

Japanese Grammar & Reading | Beginner | 1 | 1 |

Comprehensive Japanese | Beginner | 5 | 4 |

Japanese Composition | Pre-intermediate | 2 | 2 |

As noted above, the main objective of this study is to examine the structure, design, and challenges of online Japanese language classes. To achieve this, the analysis focused on various elements at each institution, including learner demographics (age), course titles, teaching duration, learning goals, Japanese proficiency levels, linguistic knowledge and skills, instructional formats, teaching materials, learning management systems (LMS) and platforms, lesson structure and design, classroom activities, instructional challenges, key considerations, and suggested improvements.

6. Results

6.1. On Lesson Formats

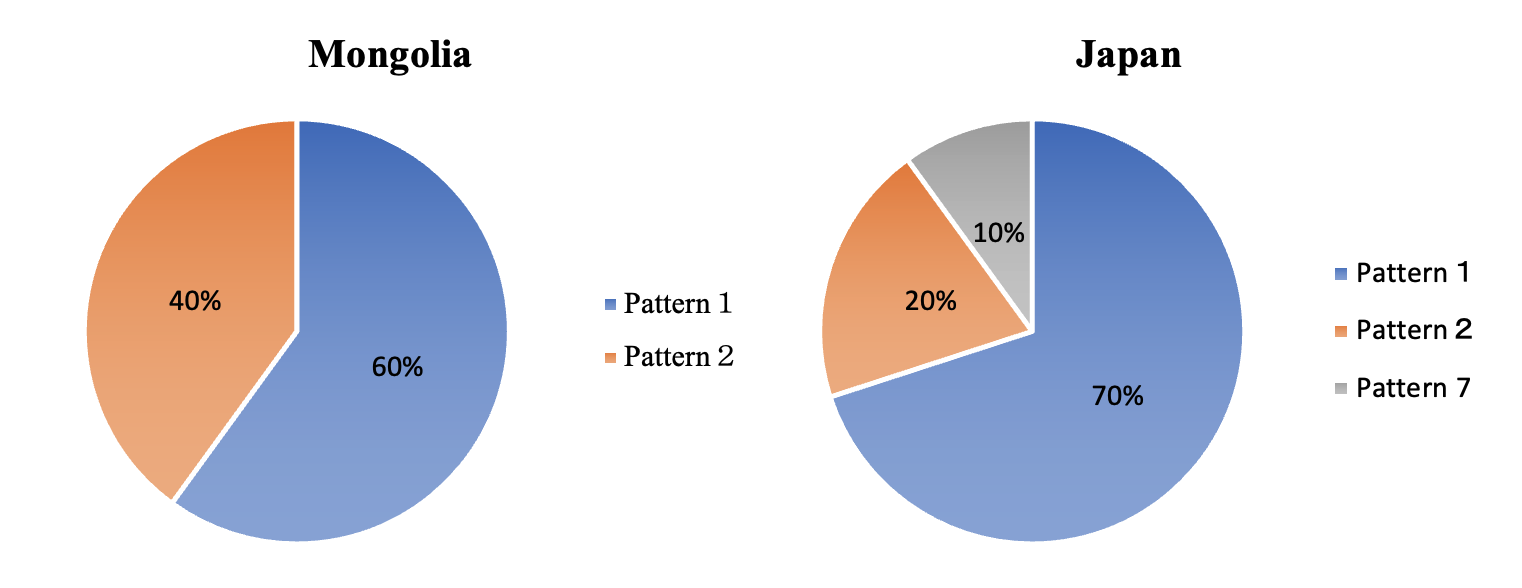

In this study, online lesson formats were categorized into four types: synchronous, asynchronous, hybrid, and blended. The survey clarified which format was primarily used in each country. In Mongolia, synchronous classes accounted for 90% of the total, while in Japan, only 30% were synchronous. Instead, hybrid and blended models made up 70% of the lessons in Japan, indicating a notable difference between the two countries.

This disparity suggests that synchronous lessons were the dominant format in Mongolia. This may be attributed to Mongolian teachers attempting to replicate face-to-face classes as closely as possible in an online environment, thereby conducting synchronous sessions that followed the traditional classroom structure.

6.2. On Lesson Structure and Design

To understand teachers’ perceptions of online versus face-to-face lesson design, the survey included the question: “Compared to face-to-face classes with the same objective, how do you perceive the structure of online classes?” In response, 90% of Mongolian teachers answered “Mostly the same,” while 80% of Japanese teachers answered “Very different,” indicating a clear contrast in perspectives.

For analysis, lesson structures were examined using a framework commonly applied in Japanese language education: Pre-task → Introduction → Basic Practice → Application Practice → Post-task. Respondents were asked to select one of six preset course design patterns or describe a different structure under the “Other” option. Among the responses, the following three patterns were commonly observed:

• Pattern 1: Pre-task (offline) → Reflection (online) → Introduction (online) → Basic Practice (online) → Application Practice (online) → Homework Explanation (online) → Post-task (offline)

• Pattern 2: Reflection (online) → Introduction (online) → Basic Practice (online) → Application Practice (online) → Homework Explanation (online) → Post-task (offline)

• Pattern 7: Reflection (online) → Introduction (online) → Basic Practice (offline) → Application Practice (online) → Homework Explanation (online) → Post-task (offline)

Pattern 7 is notable for conducting the basic practice component offline. Figure 1 presents a comparison of lesson structures in Mongolia and Japan.

Figure 1 - Comparison of Lesson Structures in Mongolia and Japan

6.3. On Difficulties and Challenges

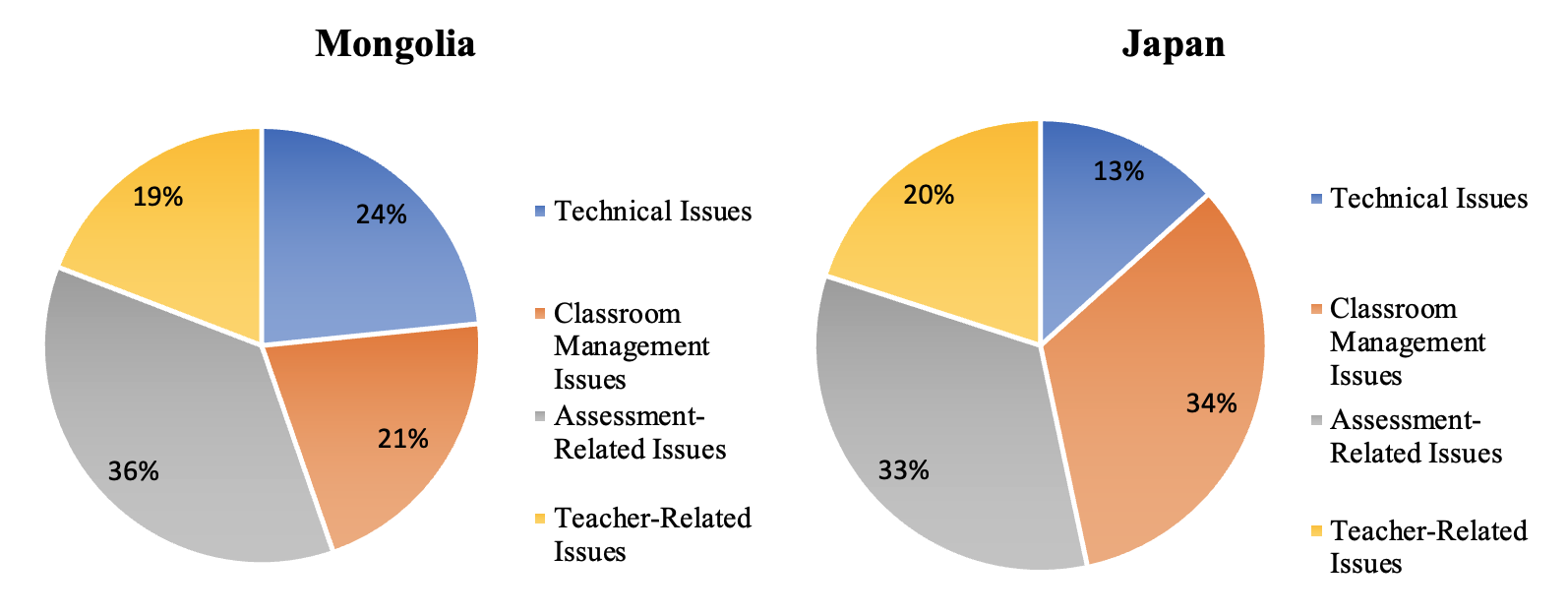

In this study, open-ended responses were collected regarding the difficulties encountered when conducting online lessons. The responses were categorized into the following four areas:

1. Technical Issues (Inadequate equipment, Unstable internet connections, Background noise, Challenges in using systems and platforms, etc.)

2. Classroom Management Issues (Lessons did not proceed as planned, Difficulty in communicating with students, Inability to maintain learner concentration, Difficulty in assessing learner understanding, Inability to track overall student participation, Learners' passivity, Learners unfamiliar with collaborative learning, resulting in uneven participation, Insufficient class time, etc.)

3. Assessment-Related Issues (Difficulty in checking homework, Inadequate opportunities for reflection, Time-consuming evaluation, Concerns about the credibility of learners’ independent test-taking, etc.)

4. Teacher-Related Issues (Disruption of work-life balance, Increased workload, Time-consuming lesson preparation (e.g., video creation), Copyright concerns, Need to revise content, as face-to-face lessons could not be directly applied to online formats, etc.)

Figure 2 presents a comparison of difficulties and challenges in Mongolia and Japan.

Figure 2 - Comparison of Difficulties and Challenges in Mongolia and Japan

6.4. On Key Considerations in Teaching

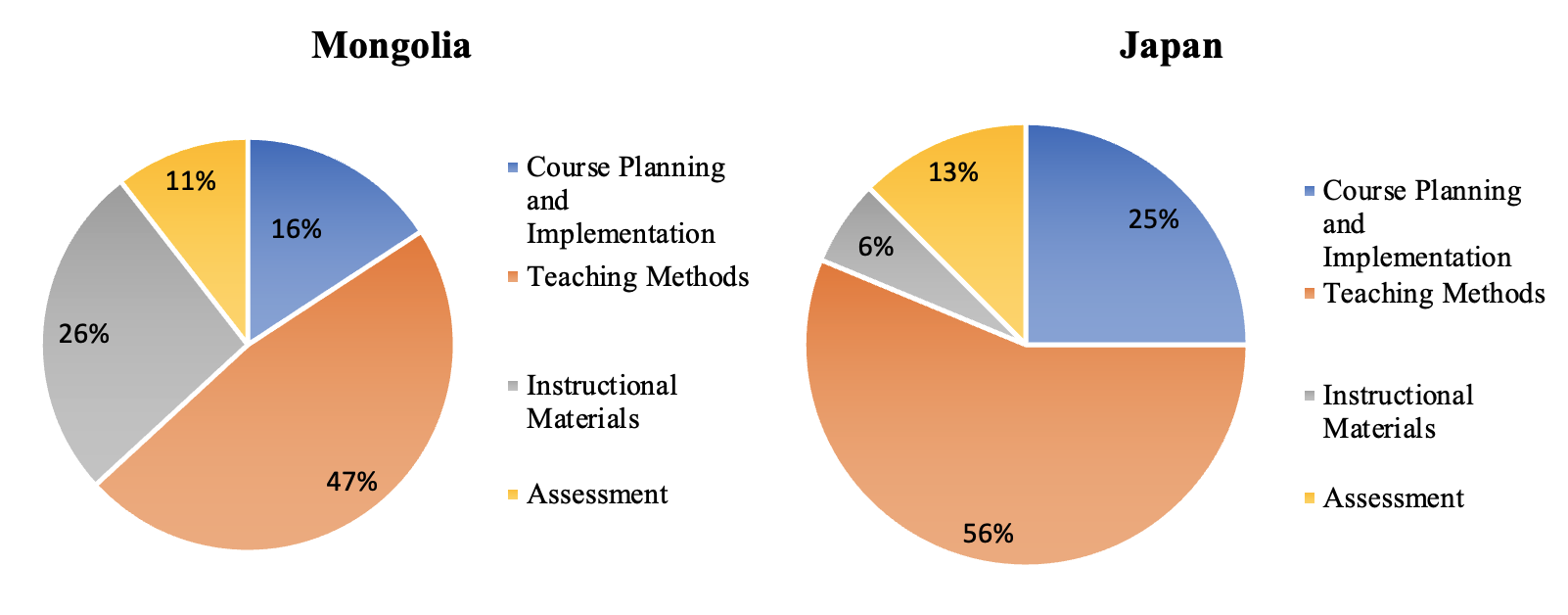

The questionnaire included an open-ended question asking teachers to describe the aspects they paid the most attention to when conducting online classes. The responses were categorized into four areas:

1. Course Planning and Implementation.

2. Teaching Methods.

3. Instructional Materials.

4. Assessment.

Figure 3 presents a comparison of key considerations in Mongolia and Japan.

Figure 3 - Comparison of Key Considerations in Mongolia and Japan

In Mongolia, particular emphasis was placed on creating appropriate instructional materials and adapting existing materials to suit online environments. On the other hand, Japanese teachers focused more on lesson planning and design, stating that they designed their classes to develop learners’ autonomous learning skills and, even when the same activities could not be conducted, they aimed to ensure the activities held equal educational value. This shows that Japanese teachers prioritized pedagogical creativity and innovation in lesson design over simply replicating face-to-face classroom activities.

6.5. On Suggestions for Improvement

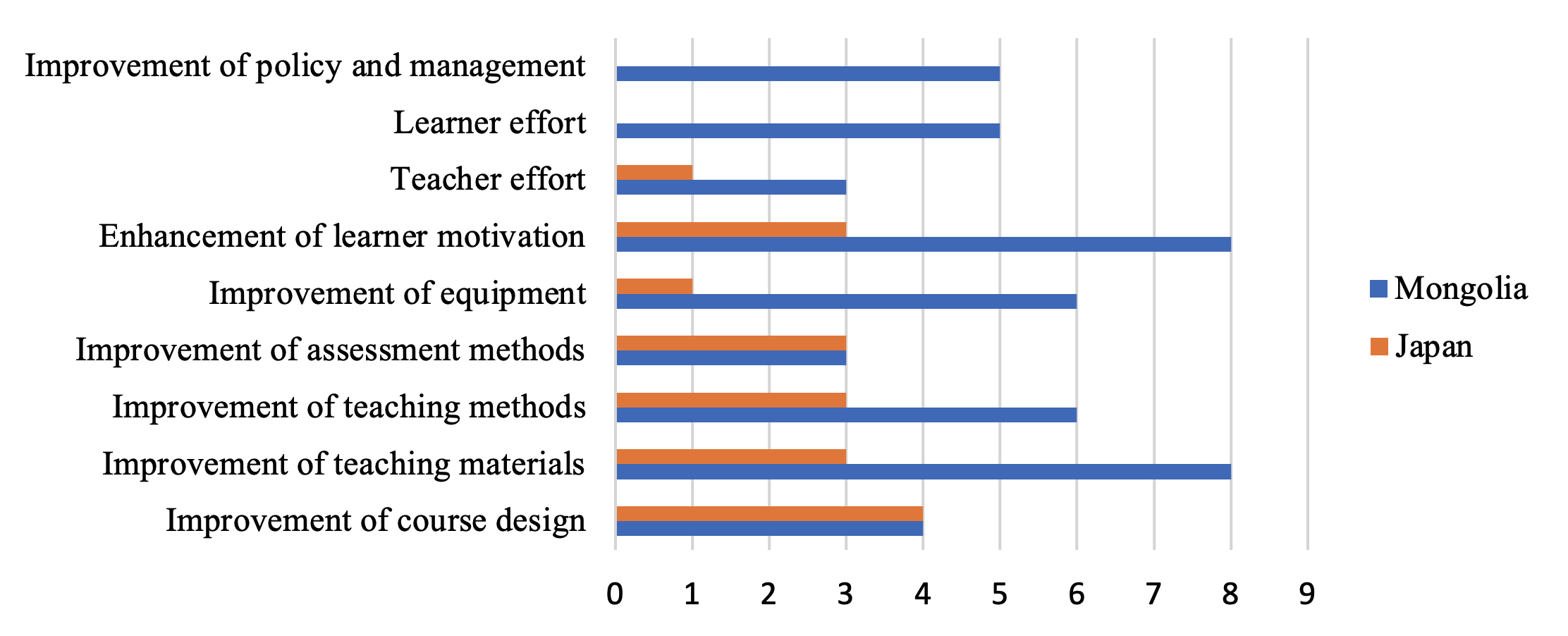

In the survey, a multiple-choice question asked teachers to select proposed improvements for future online lessons. The options included the improvement of course design, teaching materials, teaching methods, assessment methods, and equipment; the enhancement of learner motivation; increased teacher and learner effort; and the improvement of policy and management. Figure 4 presents suggestions for improving online lessons.

Figure 4 - Suggestions for Improving Online Lessons

Overall, both Mongolia and Japan were forced to shift from face-to-face to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, their approaches to lesson delivery and instructional design differed significantly. In Mongolia, many educators simply transferred the structure of face-to-face lessons to online settings. As a result, teacher workload increased, and negative impressions of distance education became widespread. Conversely, in Japan, teachers employed more flexible designs by shifting self-study elements offline and focusing on interactive activities (e.g., presentations and discussions) during live sessions or in-person meetings.

7. Discussion

Research on distance learning in the field of Japanese language education in Mongolia is still developing. While some findings, such as those presented by Javzandulam (2022), have shed light on the situation in language centers, including both benefits and limitations, academic studies covering a broader range of institutions, particularly universities, remain scarce. Reported advantages of online instruction included reduced commuting time, access to larger student groups, and increased listening opportunities through recorded materials. However, teachers also noted several disadvantages, such as low learner motivation, difficulties in assessing comprehension and engagement, and the burden of adapting content originally designed for in-person instruction .

The present study expands on this by comparing online teaching practices in Mongolia and Japan. It became evident that many Mongolian institutions delivered online lessons by closely following the structure of traditional classroom-based education. This approach did not adequately address the distinct demands of digital learning environments and often resulted in limited interactivity, reduced learner autonomy, and increased workload for teachers.

In contrast, Japanese institutions adopted hybrid and blended learning formats that strategically combined online with offline elements. These models allowed for more flexible learning experiences, better time management, and enhanced learner engagement. Rather than simply transferring existing content online, teachers in Japan designed lessons specifically suited to the strengths and limitations of remote instruction.

This comparison suggests that for Mongolia to improve the quality of online Japanese language education, it is essential to move beyond direct replication of classroom formats and instead adopt instructional designs that are appropriate for digital contexts. Key areas for improvement include course planning, teaching materials, assessment strategies, and teacher development. Moreover, institutional support and collaboration among educators are critical for sustaining effective online instruction.

Adopting successful practices from Japan could help Mongolia build more adaptable, interactive, and learner-centered online education models. These insights are not only relevant to Japanese language instruction in Mongolia but also offer implications for improving distance education in similar international settings.

8. Conclusion

This study revealed that many online Japanese language classes in Mongolia were conducted by replicating the structure of traditional face-to-face lessons. As a result, numerous challenges remained unaddressed. In contrast, Japanese institutions adopted hybrid and blended formats that effectively integrated online and offline components, offering more adaptable and pedagogically sound learning experiences. To improve the effectiveness of online education in Mongolia, it is essential to move beyond the simple transfer of in-person lesson formats and instead develop course designs that provide comparable educational value through alternative structures. The successful practices observed in Japan, particularly in hybrid and blended learning, provide useful models for enhancing learner autonomy, engagement, and time management. Furthermore, this research highlights the need for careful development of teaching materials, instructional methods, and systems for managing interaction and feedback. Improvements in these areas should be approached holistically as part of a broader curriculum development process that considers learner needs, teacher capacity, delivery methods, and available resources. Ultimately, the success of online education depends on the active collaboration among teachers, learners, and facilitators. Institutions must take a proactive role in creating flexible and responsive curricula that fully utilize the advantages of digital learning environments. These findings offer valuable insights not only for Japanese language education in Mongolia but also for the future of distance education in broader international contexts.