MFCTIIF: Интеграционная платформа для многоканальной обработки данных о киберугрозах

MFCTIIF: Интеграционная платформа для многоканальной обработки данных о киберугрозах

Аннотация

Растущий объем и разнообразие потоков данных разведки киберугроз (CTI) создают серьезные проблемы для взаимодействия, согласованности метаданных и автоматизированной оценки угроз. В этой статье мы представляем MFCTIIF — интеграционную платформу многоканальной разведки киберугроз, предназначенную для агрегации, обогащения и классификации индикаторов вредоносных программ из разнородных источников. Система выполняет структурированное сопоставление данных, разрешение синонимов и автоматизированную классификацию уровня угроз, выводя потоки в формате JSON, подходящие для операций по обеспечению безопасности. Мы тестируем MFCTIIF на основе 100 последних образцов вредоносных программ, показывая, что большинство из них представляют собой угрозы высокого риска, такие как RAT, и имеют постоянную задержку сквозной обработки ≈15–17 с на образец. Сравнительный анализ с четырьмя существующими решениями показывает, что MFCTIIF — единственная система, отвечающая всем семи ключевым требованиям, однако она ограничена пробелами в метаданных и дисбалансом классификации для неизвестных угроз. Для решения этой проблемы мы предлагаем будущие усовершенствования, включая автоматизированный маппинг к формату STIX с помощью LLM моделей, классификацию на основе LLM, нечеткое сопоставление и параллельное кэширование для улучшения покрытия и уменьшения задержек.

1. Introduction

Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) is a structured form of cybersecurity information aimed at providing organizations with critical insights about emerging and existing cyber threats

. Such intelligence typically includes data about malicious indicators, tactics, techniques, and procedures used by cyber adversaries, enabling organizations to proactively manage their cybersecurity posture in alignment with internationally recognized frameworks such as the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework , and the EU Directive on security of network and information systems .As the scale of cyberattacks continues to escalate, so does the urgency to respond with timely, actionable, and shareable threat intelligence. According to recent statistics, in 2024 alone there were over 6.06 billion malware attacks globally

, while on average it takes 194 days to identify a data breach and the Cam4 case holds the record for the largest data breach of all time with over 10 billion compromised accounts .Sharing CTI between organizations significantly enhances their collective defense capabilities and situational awareness

, . When one entity experiences a cyber-attack, the knowledge gained can aid other entities in managing similar cyber-threats , . To ensure efficient interoperability , CTI commonly employs standards for delivery mechanism, such as TAXII and content format such as STIX by OASIS which is aligned with MITRE ATT&CK attack patterns . Some works propose using TAXII standard with a blockchain has been proposed to ensure privacy, data integrity and interoperability in CTI sharing , . However, despite the rise of threat intelligence platforms (TIPs), most organizations fail to operationalize CTI effectively across their infrastructure. The interoperability problem is well-documented in the literature. Rantos et al. provided a comprehensive account of interoperability challenges in CTI ecosystems, identifying syntactic mismatches, semantic inconsistencies, and governance-level fragmentation as persistent barriers. They emphasize that CTI is not only difficult to exchange but also hard to align across heterogeneous systems. This reveals not only a technical gap, but a deeper systemic failure in CTI integration and interoperability across diverse sources and systems.To address these gaps, we propose the MFCTIIF — Multi‑Feed Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Framework, a modular system designed to unify multi-source CTI and enhance its operational value. The contributions of this work are as follows:

1. Unified multi-source integration for heterogeneous indicators. MFCTIIF automatically ingests and harmonizes indicators from multiple CTI feeds

, , addressing the heterogeneity challenge.2. Metadata enrichment for effective risk prioritization by aggregating auxiliary attributes such as AV detections, malware family classifications, and contextual threat tags, MFCTIIF enriches sparse raw indicators.

3. Automated threat-level assessment and actionable CTI output. MFCTIIF incorporates a lightweight analytics module that computes a threat severity score based on frequency and classification of observed malware samples.

4. Empirical benchmarking on recent malware samples. We evaluate MFCTIIF on the 100 latest malware samples from MalwareBazaar, demonstrating its effectiveness in unifying multi-source CTI, enriching sparse indicators, and providing actionable threat-level assessments in real-world conditions.

By combining multi-source integration, semantic enrichment, and automated threat assessment, MFCTIIF converts fragmented and underutilized threat indicators into coherent, high-value intelligence. This enables security operations centers (SOCs) to improve decision-making and reduce mean time to response (MTTR).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the methodology, beginning with the mathematical model of multi‑feed CTI integration (Section 2.1) and the system architecture (Section 2.2), followed by detailed descriptions of the import (Section 2.3), data matching (Section 2.4), analytics (Section 2.5), and export modules (Section 2.6). Section 3 provides the evaluation, including measurements of average API response time (Section 3.1), end‑to‑end latency per sample (Section 3.2), and analysis of sample characteristics (Section 3.3), threat level calculations (Section 3.4), and family distribution (Section 3.5). Section 4 presents the discussion, highlighting the key findings (Section 4.1) and outlining directions for future research (Section 4.2). Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and summarizes the key contributions, with references provided at the end.

2. Methodology

This section describes the design and operation of the MFCTIIF framework, covering its mathematical foundation, architecture, and core modules. Section 2.1 introduces the mathematical model, formalizing the mapping of malware samples to hashes, families, and threat levels. Section 2.2 presents the system architecture, outlining the workflow from data ingestion to threat-level output. Sections 2.3–2.6 describe the four core modules: the Import module for multi‑feed ingestion, the Data Matching module for metadata alignment, the Analytics module for automated threat assessment, and the Export module for producing structured JSON feeds.

2.1. Mathematical model

To systematically unify heterogeneous cyber threat intelligence (CTI) feeds and support automated threat assessment, we define a formal mathematical model. This model captures malware samples, their associated attributes, probabilistic detection behavior, and temporal evolution, forming the analytical foundation of the MFCTIIF framework. Let the following sets to represent the principal entities in multi-feed CTI analysis:

-

-

-

-

-

To relate malware samples to their features, we define four key mapping functions:

1. Cryptographic identity: maps each malware sample to its SHA-256 hash, providing a unique identifier for feed unification.

2. Signature mapping: associates a sample with the set of signatures collected from av engines and external sources, where P is a power set.

3. Family mapping: assigns each sample to one or more malware families, supporting lineage-based context enrichment.

4. Threat level classification: maps class information to a final severity level, consolidating lineage-based context enrichment.

Each malware sample

Where

Then, given a sample which belongs to Adware, RiskTool, and Rootkit, we have:

To incorporate detection reliability, we define the detection probability (8) for a malware sample

Where

For each sample

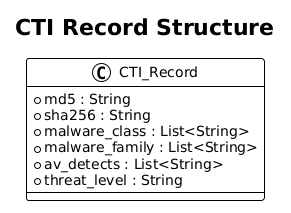

This tuple serves as the canonical representation of a threat indicator in the MFCTIIF framework. The complete threat feed is then expressed as:

Finally, combining the above, the multi-feed CTI integration model is represented as:

2.2. System architecture

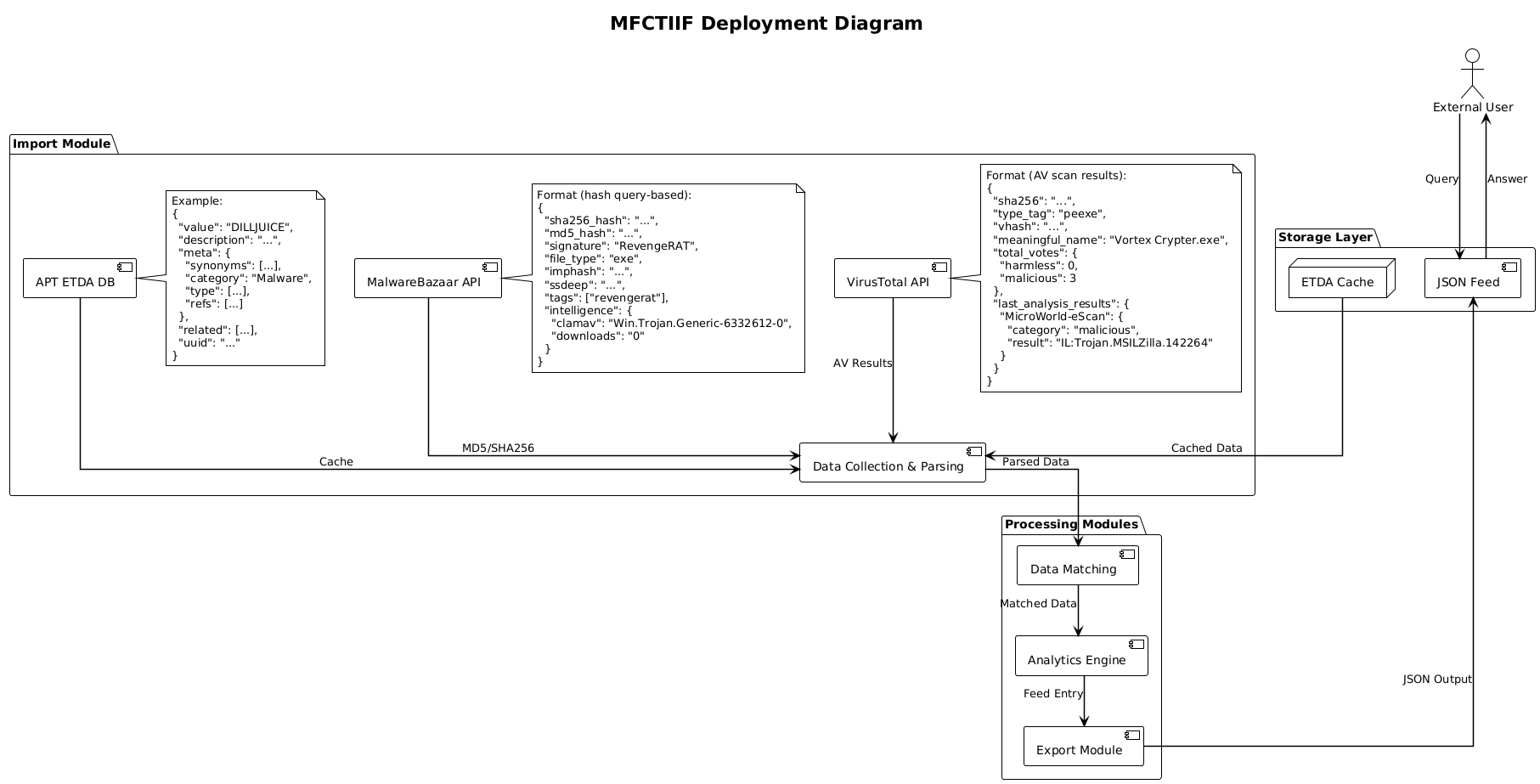

The system architecture operationalizes the mathematical model introduced in the previous section by implementing a complete multi-stage CTI processing pipeline. Each stage in the workflow corresponds to a function of the model: cryptographic identification, classification and enrichment, threat assessment, and final feed export. Figure 1 shows the deployment diagram of the MFCTIIF, illustrating the interaction between external data sources, internal processing modules, the cache, and the output feed.

Figure 1 - MFCTIIF deployment diagram

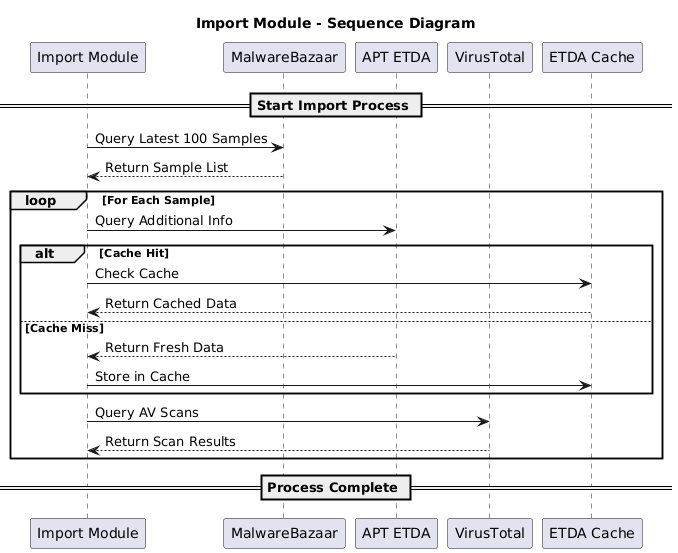

2.3. Import module

The workflow begins with the Import Module (Figure 2), which collects malware samples from multiple sources, including MalwareBazaar, VirusTotal, and the APT ETDA database. For each batch of new samples, the system first checks the ETDA cache to avoid redundant queries. If the requested data is unavailable, fresh metadata is retrieved from the ETDA database and stored in the cache for subsequent lookups. Simultaneously, the module queries VirusTotal to gather AV scan results for each sample. This stage ensures that every sample entering the pipeline has both its cryptographic identity and associated threat intelligence collected before handing the samples to the next stage.

Figure 2 - Import module sequence diagram

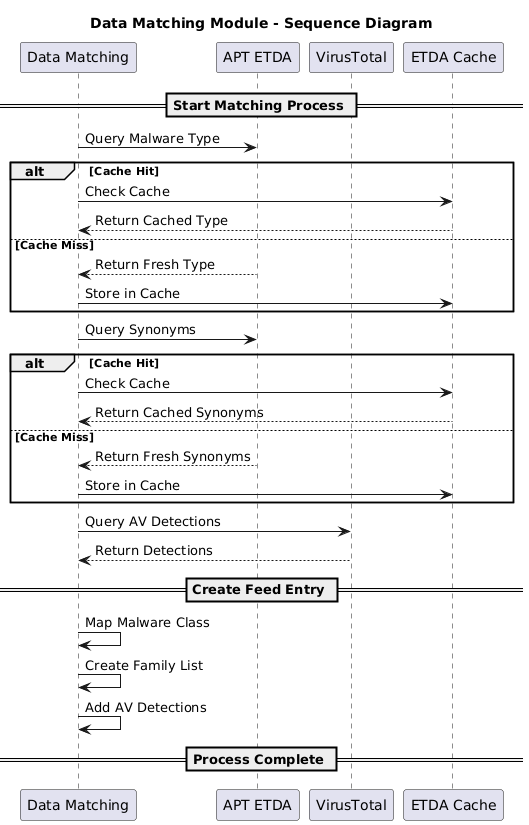

Once raw samples are imported, the Data Matching Module (Figure 3) enriches the data context by identifying malware classifications and their synonyms. This stage performs two ETDA queries for each sample: one to classify the malware type and another to retrieve synonym relationships. Both queries follow the same cache-first strategy — cached results are used when available, and new results are fetched and stored when cache misses occur. After the ETDA lookups, the module performs internal processing to map malware classes, create family lists, and associate AV detections with the appropriate families — forming the core feed entry for the next stage.

Figure 3 - Data matching module sequence diagram

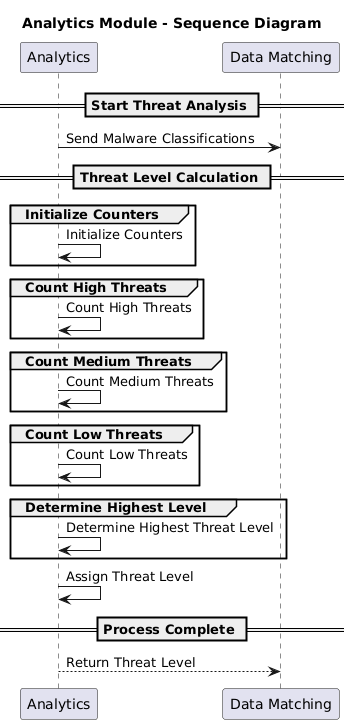

The Analytics Module (Figure 4) performs threat level assessment based on the enriched feed entries provided by the Data Matching Module. The core logic focuses on computing the highest observed threat level among the collected indicators. Counters are initialized for high, medium, and low threat categories, each incremented based on the classifications in the feed entry. The final threat level corresponds to the maximum observed category and is then attached to the sample record. At the end of this stage, the feed entry is fully enriched with a computed threat level and is ready for export stage.

Figure 4 - Analytics module sequence diagram

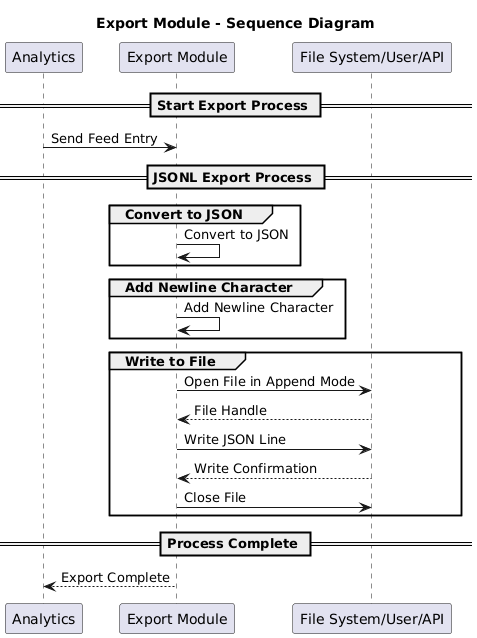

The final stage of the workflow (Figure 5) is handled by the Export Module, which converts enriched feed entries into the JSON format for distribution. Each feed entry is transformed into a JSON object, appended with a newline character, and written to the output file in append mode to preserve history. The module also handles proper file closure and confirmation of successful writes, ensuring that the feed remains consistent and incrementally updateable.

Figure 5 - Export module sequence diagram

3. Evaluation

This section evaluates the MFCTIIF framework in terms of performance and threat intelligence output quality. Section 3.1 measures the average API response time, reflecting external dependency performance. Section 3.2 reports the end‑to‑end latency per sample, highlighting workflow efficiency and occasional delays. Section 3.3 analyzes sample characteristics, focusing on metadata coverage in malware_class and malware_family. Section 3.4 presents the threat level distribution, while Section 3.5 examines the malware family distribution.

3.1. Average API response time

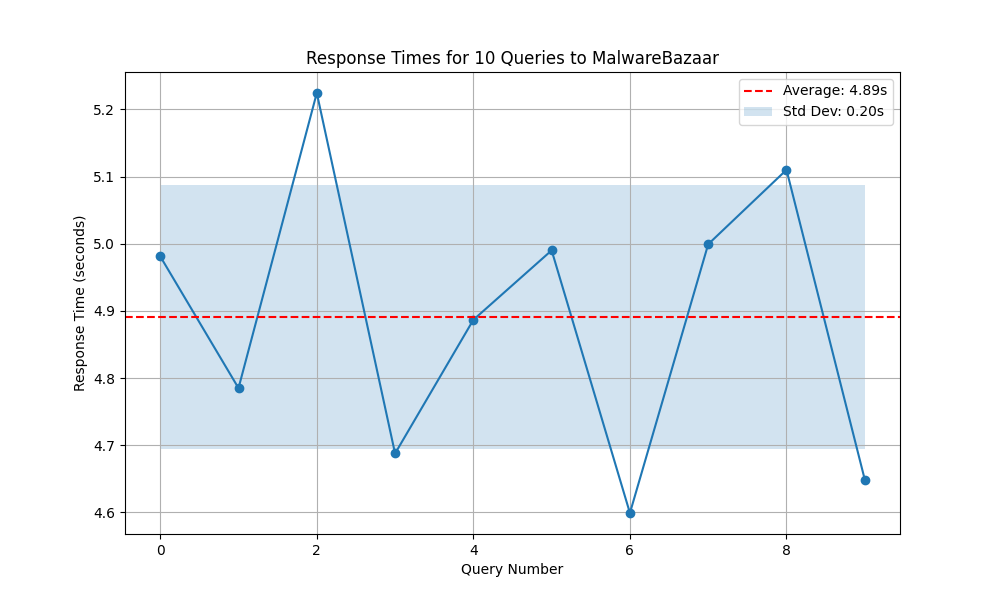

Figure 6 illustrates the response times for 10 consecutive queries submitted to the MalwareBazaar’s “get_recent” API. The horizontal axis represents the sequential query index, while the vertical axis shows the measured latency in seconds. Each blue marker denotes the individual response time of a single query, and the connecting line highlights the temporal variation across the series of requests.

Figure 6 - MalwareBazaar get_recent timings for 100 samples

3.2. End to end latency per sample

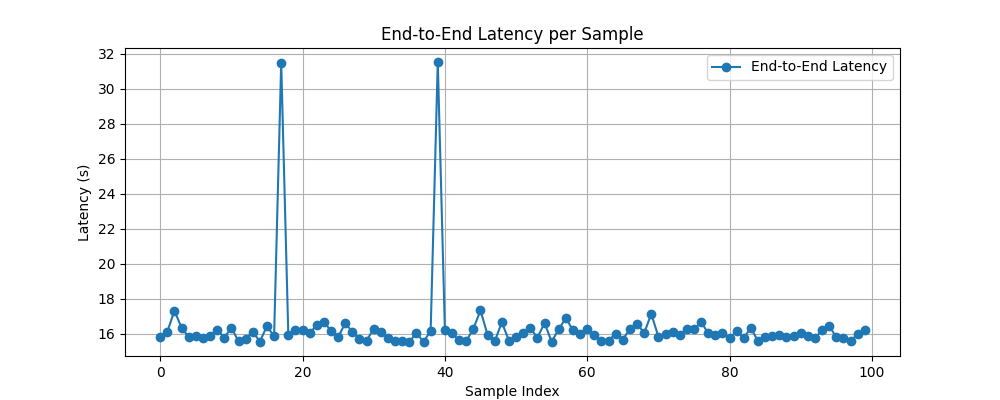

Figure 7 shows the end-to-end latency for processing 100 malware samples through the MFCTIIF pipeline. Most samples complete within 15–17 seconds, forming a stable baseline for import, data matching, analytics, and export. This indicates that the workflow is generally efficient and predictable under normal conditions.

Figure 7 - End to end latency per sample

3.3. Samples characteristics

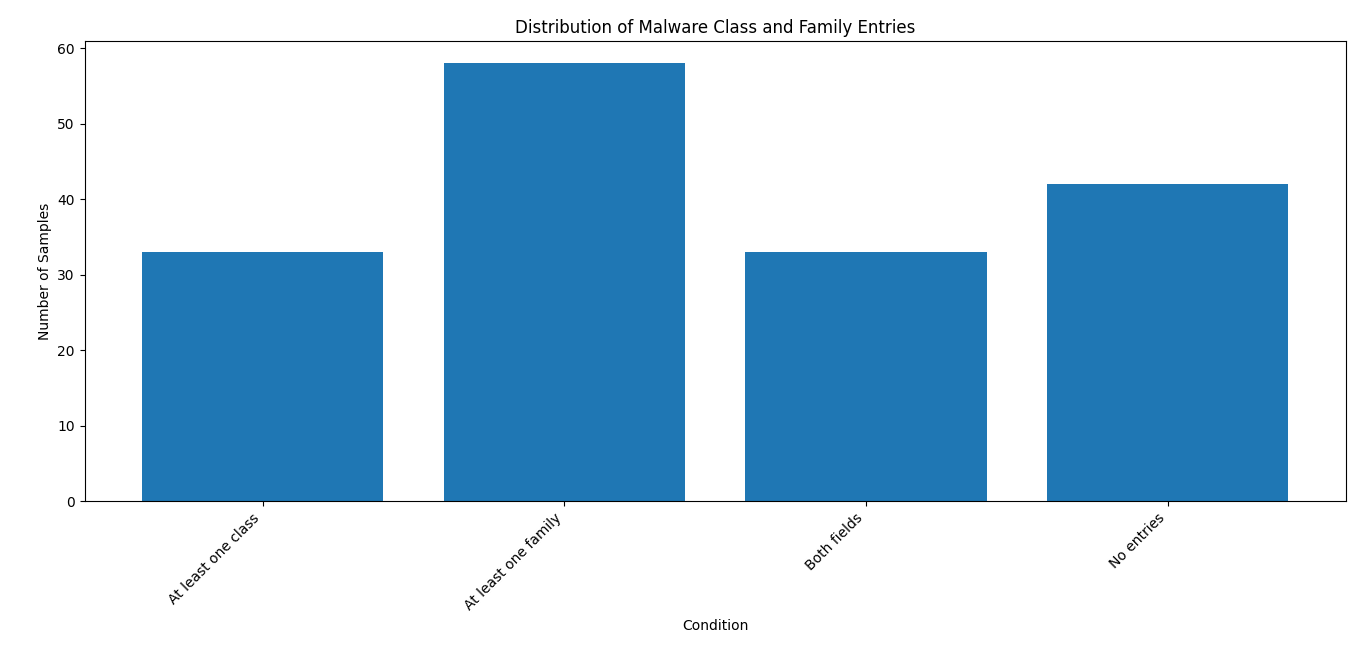

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution of the latest 100 malware samples based on the presence or absence of metadata entries in two key fields: malware_class and malware_family. These fields are critical for downstream analytics, particularly for the threat level assessment component of the system.

Figure 8 - Sample characteristics distribution

3.4. Threat level calculation

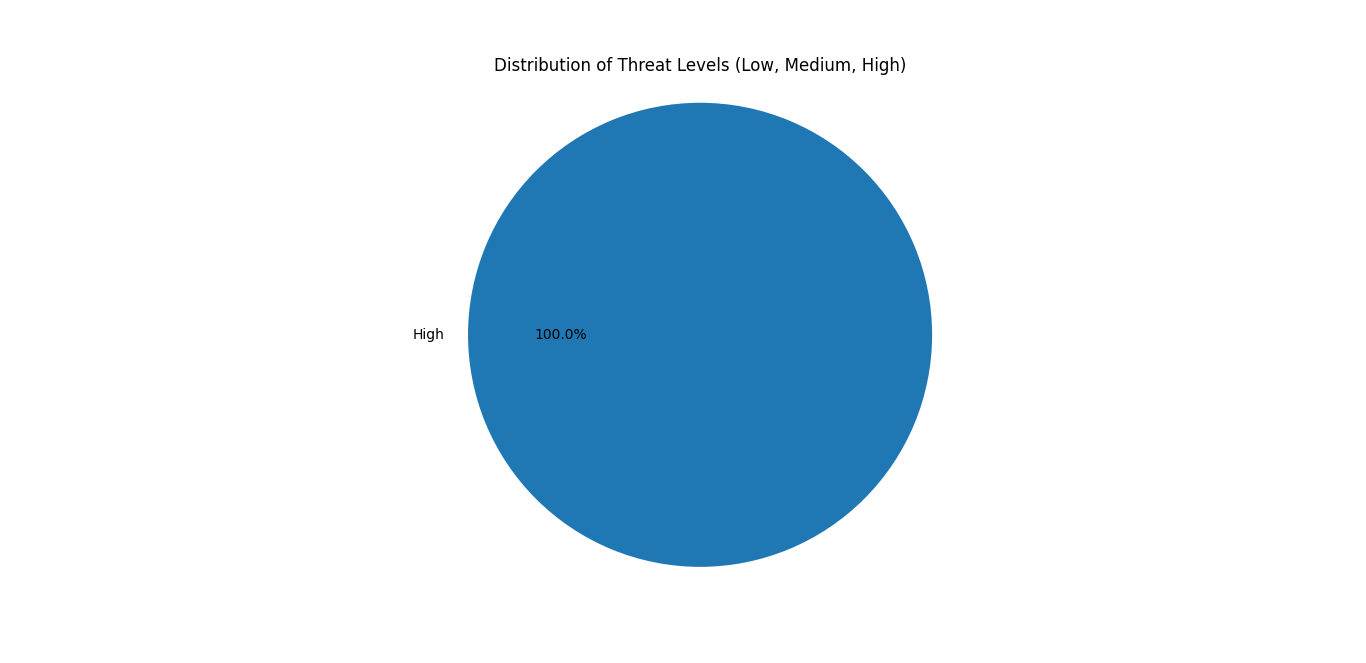

The distribution shown in Figure 9 is a direct consequence of the metadata coverage illustrated in Figure 8. As demonstrated previously, 42% of the analyzed samples lack entries in both the malware_class and malware_family fields, and only 33% contain valid class information required for threat level computation. This absence of classification metadata forces the analytics module to either omit threat scoring or rely solely on fallback detection-to-class mapping.

Figure 9 - Threat level distribution in recognized samples

3.5. Family Distribution

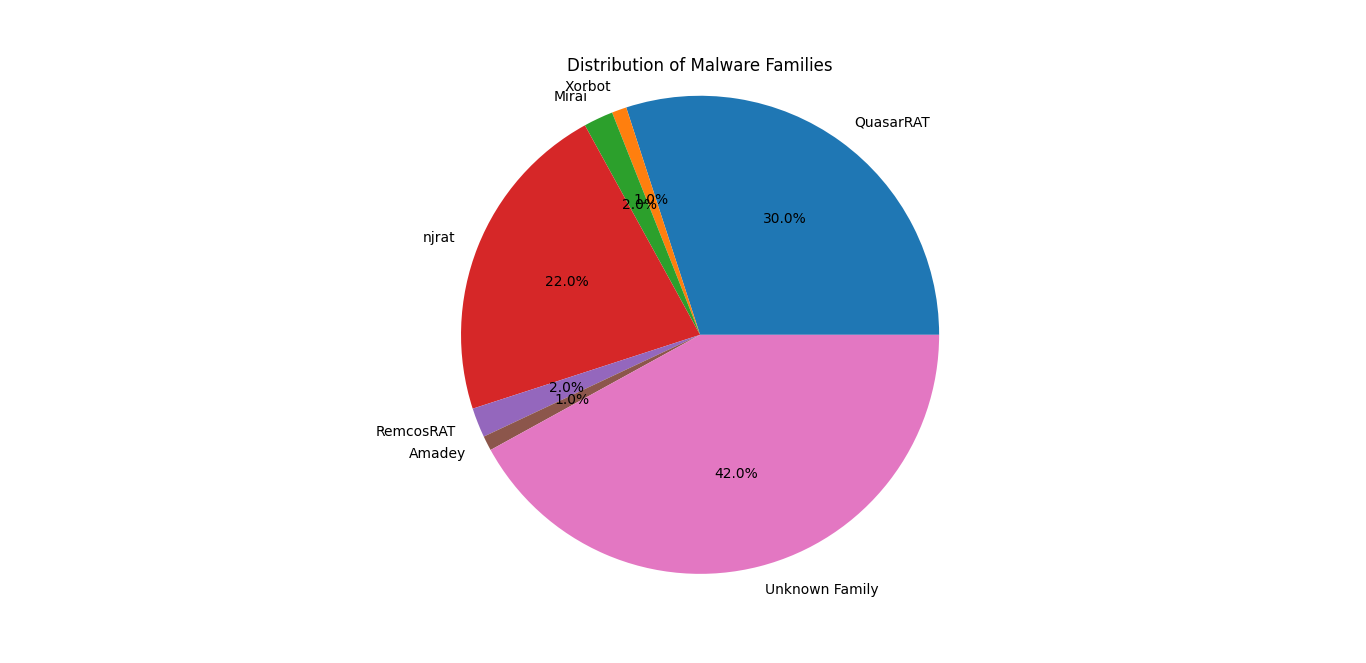

Finally, Figure 10 illustrates the distribution of malware families within the analyzed dataset, highlighting both prevalent and less common threats. The most dominant malware family in the dataset is QuasarRAT (30%), which is a well-known remote access trojan (RAT) capable of persistent system compromise and exfiltration of sensitive data. Its high prevalence signals that remote access threats remain a critical risk vector in the analyzed samples. Next up we have njrat (22%), also known as NetWire, is another widespread RAT family observed in the dataset. It is modular in design and capable of multiple malicious actions, including credential theft and system takeover, reinforcing the dominance of RATs in the current sample set. Mirai (2%) appears less frequently but is significant due to its history of powering large-scale IoT-based DDoS botnets. Even low prevalence in this dataset is operationally important, as Mirai infections can escalate into network-wide attacks. RemcosRAT and Xorbot (2% each) form a smaller but still notable portion of the dataset. These threats indicate a long tail of active RAT and botnet variants circulating in the wild. Amadey (1%) is among the least represented families in the dataset. Despite its low frequency, its appearance highlights the diverse composition of threats, including loader-type malware.

Figure 10 - Malware family distribution

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

The previous section evaluation of the MFCTIIF highlights its effectiveness in integrating multi-source cyber threat intelligence, while also revealing structural limitations that affect coverage and balance. The system successfully unifies feeds from MalwareBazaar, VirusTotal, and APT ETDA, producing enriched JSON outputs that enable threat assessment and prioritization, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11 - Malware sample entry

Metadata coverage, however, proved to be a decisive factor in the system’s overall performance. As shown in Figure 8, 42% of samples lacked entries for both malware class and family, which limited the analytics module’s ability to compute threat levels for the majority of samples. This deficiency directly influenced the threat level distribution presented in Figure 9, where all classified samples were assigned a high-threat level and no medium or low-level classifications were produced. The absence of a graded severity spectrum does not necessarily indicate that the dataset lacks lower-risk samples; rather, it reflects the system’s dependency on complete and consistent metadata. Samples with missing class information, or those requiring fuzzy matching and external enrichment, currently either remain unclassified or rely solely on fallback mapping derived from AV detection strings.

Operational performance analysis further demonstrated that the framework is generally efficient and predictable, with an end-to-end latency of approximately 15–17 seconds per sample under normal conditions. Two prominent latency spikes (~31–32 seconds) were observed and are attributable to VirusTotal cache misses and API rate-limiting, which are known constraints when processing uncached or newly submitted files. Although the baseline performance is acceptable for batch processing, reliance on external APIs introduces non-deterministic delays that could affect real-time alerting and large-scale feed generation.

4.2. Comparative analysis

We evaluate our work and 4 previous related works on 7 attributes, such as

1) multi‑Source CTI Integration;

2) heterogeneous Feed Support (MalwareBazaar / VT / ETDA);

3) metadata Enrichment (Families + Signatures);

4) automated Threat‑Level Classification;

5) standardized / Actionable Output (JSON/STIX/KG);

6) latency / Performance Evaluation;

7) empirical Evaluation on Recent Malware Samples, as shown in Table 1.

Rastogi et al. in MALOnt focuses on semantic enrichment and ontology-driven knowledge graph construction for malware threat intelligence

1) it aggregates data from multiple threat reports;

2) supports general heterogeneous sources, but not specific to MalwareBazaar/VT/ETDA;

3) it also includes malware families, characteristics, attacker groups;

4) but does not assign low/medium/high threat levels;

5) it provides knowledge-graphs only, not JSON or STIX output;

6) neither does it perform timing nor latency analysis;

7) finally, it is evaluated on annotated reports, not live malware feeds;

Okazaki et al., 2024 system integrates multiple AV engines for collaborative detection using VirusTotal:

1) it supports collaborative multi-AV integration;

2) and has partial support for VirusTotal and MalwareBazaar;

3) metadata focus is on AV voting, not family or signature enrichment;

4) it outputs malicious/benign verdict, but has no severity scoring;

5) it provides detection result only, not JSON/STIX output;

6) it collects recall and weighted voting performance, but not latency.

7) it drives recall evaluation on real 7-day continuous sets of samples from MalwareBazaar.

Gao et al., 2024 ThreatKG uses AI techniques to unify structured/unstructured OSCTI and construct a threat knowledge graph (KG) with rich context:

1) it aggregates OSCTI from many sources;

2) but has no VT/MB/ETDA ingestion;

3) it extracts TTPs, entities, relations;

4) and has no explicit threat level scoring;

5) it uses knowledge graph and no JSON/STIX;

6) finally no runtime nor latency evaluation and;

7) no per‑sample malware feed evaluation.

Rastogi et al., 2023 TINKER captures multi‑source OSCTI and also builds a CTI Knowledge Graph (CTI‑KG) like ThreatKG:

1) it aggregates multi‑modal OSCTI (blogs, reports, CVEs, GitHub feeds);

2) but has no direct API‑level support for MB/VT/ETDA;

3) enrichment with entities, malware families, relationships;

4) but no threat level scoring;

5) it uses knowledge graph only, no JSON or STIX export;

6) nor does it run latency or runtime evaluation;

7) evaluated on curated CTI reports and triple inference, not live malware feeds.

Table 1 - Comparative analysis table

Ref. | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

+ | - | + | - | KG | - | - | |

+ | + | - | - | - | + | + | |

+ | - | + | - | KG | - | - | |

| + | - | + | - | KG | - | - |

MFCTIIF | + | + | + | + | JSON | + | + |

Despite demonstrating functional success in Table 1 over related works, MFCTIIF exhibits several current limitations. The framework is constrained by incomplete metadata, which produces gaps in class and family resolution, and leads to a skewed threat level distribution dominated by high-severity classifications. External API dependencies introduce sporadic latency spikes, reducing throughput and predictability. Also, the reliance on signature-driven classification and exact CTI mappings limits its ability to handle emerging, obfuscated, or zero-day malware, leaving a portion of samples unclassified and reducing the feed’s overall coverage. To address these issues, we propose some future research directions below.

4.3. Directions for future research

We now highlight several directions for future research that can enhance the capabilities, coverage, and operational resilience of the MFCTIIF. These directions focus on improving metadata completeness, classification accuracy, and system performance, thereby addressing the current constraints of metadata gaps, skewed threat distributions, and external API latency.

First, standardizing output using STIX (Structured Threat Information eXpression) will improve interoperability with existing CTI platforms and automated threat‑sharing ecosystems. By expressing threat indicators, malware families, and associated attributes in STIX format, the framework could seamlessly integrate with TAXII servers and external SOC tooling. Standardization would also facilitate structured reasoning over indicators and relationships in downstream pipelines

, . In future iterations, automated mapping to STIX could be supported by LLM‑based models, which have demonstrated strong performance in extracting CTI entities and generating machine‑readable threat reports, as shown in AZERG .Second, classification accuracy and coverage can be improved by integrating machine learning (ML) and large language models (LLMs) to infer malware classes and threat levels for samples with missing or incomplete metadata. LLMs have recently shown strong utility in CTI contexts, such as classifying threat reports and enriching indicators with contextual labels

, . In combination with heuristic and keyword‑based extraction from AV detections, these methods can address the classification imbalance observed in Figures 8 and 9, producing a more nuanced distribution of low, medium, and high‑threat samples.Third, system performance and scalability can be enhanced through improved caching strategies and task parallelization. Our latency benchmarks demonstrate that end‑to‑end processing is dominated by the import stage due to VirusTotal rate‑limiting. Leveraging persistent caching and parallel execution of API requests could reduce latency spikes and improve batch throughput, a technique widely applied in high‑performance data pipelines.

Finally, the adoption of fuzzy matching and similarity metrics can address structural gaps in metadata mapping. Current ETDA lookups depend on exact or near‑exact signature matches, leaving many samples unclassified. Implementing Levenshtein distance

or Python’s difflib ratio for family and signature mapping can significantly improve coverage by detecting misspellings, minor variations, or obfuscated names in threat feeds . Extending this approach to AV detection strings could further enhance threat scoring for previously “unknown” samples.5. Conclusion

This paper presented the MFCTIIF — Multi‑Feed Cyber Threat Intelligence Integration Framework, designed to address interoperability and enrichment challenges in multi‑source cyber threat intelligence. By integrating feeds from MalwareBazaar, VirusTotal, and APT ETDA, the framework performs automated data matching, family and class resolution, and threat‑level assessment, producing structured JSON outputs suitable for SOC operations. Evaluation on 100 recent malware samples demonstrated that the system reliably identifies high‑risk threats, dominated by RATs and banking trojans, with a stable 15–17 second end‑to‑end latency and occasional API‑induced spikes.

A comparative analysis against four representative CTI aggregation and enrichment frameworks highlights that MFCTIIF is the only approach covering all seven evaluation attributes, including multi‑feed integration, heterogeneous feed support, metadata enrichment, automated threat scoring, actionable outputs, latency evaluation, and empirical testing on live malware samples.

Despite these promising results, the framework’s current impact is limited by metadata gaps, classification imbalance, and external API dependencies, which leave a portion of samples unclassified or skew threat scores toward high severity. Future enhancements should focus on STIX/TAXII standardization, ML/LLM‑driven classification for unknown samples, improved caching and parallelization, and fuzzy metadata matching to expand coverage and reduce latency. These improvements will enable MFCTIIF to evolve into a low‑latency, AI‑augmented CTI pipeline, further strengthening its value for operational cybersecurity and threat response.