ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS BEHIND RUSSIA’S CLIMATE POLICY DEVELOPMENT

Кокорин A.O.

Руководитель программы “Климат и энергетика”, кандидат физико-математических наук, WWF России

ЭКОНОМИЧЕСКИЕ И ЭКОЛОГИЧЕСКИЕ ФАКТОРЫ РАЗВИТИЯ КЛИМАТИЧЕСКОЙ ПОЛИТИКИ РОССИИ

Аннотация

Проведено исследование экономических и экологических факторов, которые подразделяются на старые, которые действовали, когда у страны были обязательства по выбросам парниковых газов по Киотскому протоколу, и на новые, определяемые принципами нового соглашения ООН по проблеме изменения климата и действиями ведущих стран. Сравнительный анализ с другими странами BRICS показал, что такие факторы Киото как международная торговля квотами и сильные обязательства по выбросам сейчас не важны, их повторная активизация возможна через 10-15 лет. Важнейшим фактором остается повышение энергоэффективности. Рассмотрен широкий спектр новых факторов, среди которых адаптация к изменениям климата, отчетность по выбросам на уровне предприятий, цена углерода для долгосрочных бизнес-планов, национальные и локальные действия по углеродному регулированию. Россия идет по тому же пути климатической политики, что и другие страны BRICS, но в силу топливной направленности экономики отстает от них, временной лаг оценивается как 5-10 лет. Для ВИЭ временной лаг будет существовать еще многие годы. Другие факторы уже имеют предпосылки сокращения отставания. Реализация предпосылок требует инноваций, в частности, регулирования выбросов СО2 как инструмента внедрения новых технологий; а также мер адаптации.

Ключевые слова: Климатическая политика, выбросы СО2, экономические инструменты, энергоэффективность, адаптация к изменениям климата.

Kokorin A.O.

Head of the Climate and Energy Program, Ph. D in Physics and Mathematics WWF Russia

ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS BEHIND RUSSIA’S CLIMATE POLICY DEVELOPMENT

Abstract

This research explores economic and environmental factors, which include old drivers that were in force when Russia had greenhouse gas emissions commitments under the Kyoto Protocol, and new factors that are determined by the principles of the new UN climate change agreement and activities of the leading economies. A comparative analysis with other BRICS countries has shown that Kyoto factors, such as international emissions trading or strong emission reduction commitments, are not important at the moment, their re-activation is possible in 10-15 years. However, energy efficiency remains a most important factor. A large variety of new factors have been explored, including adaptation to climate change, emissions reporting by enterprises, carbon pricing for long-term business plans, national and local carbon regulation. Russia is going by the same road in climate policy, as the other BRICS countries, yet is lagging behind due to its energy-oriented economy; the lag is assessed at 5-10 years. In renewable energy sources the lag will be observed for many more years, whereas for other factors there are certain preconditions for catching up. If these preconditions are to work out, innovations are required, in particular, regulation of CO2 emissions as an instrument for the deployment of new technologies and adaptation measures.

Keywords: Climate policy, СО2 emissions, economic instruments, energy efficiency, adaptation to climate change.

The years 2013 – 2014 is the beginning of transition period of from the Kyoto Protocol “era” that ended in 2012 and the “new time” governed by a new UN climate agreement [1, 7, 9]. The agreement should be adopted in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) late in 2015 with entry into force from 2020; 5 years are allocated for regulatory acts and ratification [22]. In order to understand the factors behind the climate policy development, it seems practical to compare Russia to other BRICS countries. Below factors that have been driving climate policy for a long time are described first, followed by a discussion of relatively new ones.

“Old” factors behind the climate policy

Renewable energy sources (RES) development

Global development of RES sources is really impressive. However, it is mostly driven by the scarcity of domestic hydrocarbons. The climate factor, too, definitely has a role to play: in particular, in Scandinavian countries, where all people aspire to stop anthropogenic impact on the climate system. However, energy remains the most important factor of all. Domestic electricity and fuel prices coupled with the accessibility of energy resources and their role in addressing social problems in a number of countries, including Russia, delay fast development of RES from the 2010’s to later decades [2,3,14,16].

“Deep decarbonization” scenarios were simultaneously developed in 2014 for 15 largest economies building on uniform global price parameters [16]. In Russia, development of RES is delayed beyond 2025. Complete decarbonization of the electricity sector by 2050 is feasible, but mostly through the carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. Therefore in Russia, the share of RES (including large hydro plants) in 2050 electricity generation is only 50% (versus 16% at present, including 15% by large hydro). Decarbonization trajectory over 2030-2050 will ensure 20% increase in the share of RES.

The government does not see any problem in the slow growth of renewable energy use and is refraining from any action until a new RES / fossil fuel cost ratio appears in future [14]. The fast growth of RES in other BRICS countries, particularly in China, is not yet perceived as a real risk of Russia’s technological inferiority, although this risk is being largely discussed. RES development, which is an “old” and currently global trend, is unlikely to become a driver for Russia’s climate policy in the coming years.

Energy efficiency improvement

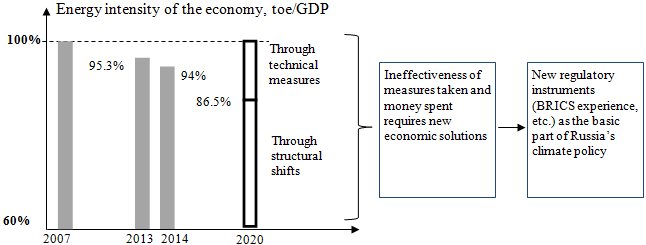

In 2007, the intention was to improve Russia’s energy efficiency by 40% by 2020; however, this is running far behind schedule [2, 12, 14]. An increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2010-2011 shows that no advantage was taken for energy efficiency during the economic recovery [9]. Nevertheless, some data show certain progress. According to the RF Ministry of Energy, in 2013 energy intensity was 4.7% below the 2007 level, and 6% cumulative reduction is expected in 2014, Fig. 1 [14]. International Energy Agency estimates energy intensity reduction as about 30% over 2000-2011. Specific СО2 emissions per GDP (kg CO2/USD GDP РРР) over the same period dropped from 1.16 to 0.79 [4].

Fig. 1 - Attainment of energy efficiency goals to 2020: dynamics and related impacts on the climate policy

Source: based on data from [5, 14]

Energy efficiency improvement remains the main “old” driver for the climate policy in all BRICS countries. However, Russia is different in the impact of energy policy on climate issues. For example, in China and South Africa measures aiming at the energy sector development integrate ambitious energy efficiency targets and then shape the core of the climate policy. In Russia the situation is different: lack of due effect from the national energy efficiency investment and misapprehension of how to remedy the situation make search for new solutions, including climate policy and carbon regulation tools [2, 5, 14]. Low effect of the national energy efficiency measures makes the government to consider a domestic climate policy.

International commitments and the country image

Historically, the country image was the first factor to encourage Russia’s climate policy development [8]. The RF President has many times highlighted Russia’s key role in the Kyoto Protocol, which in the past was very important to develop climate issues globally. Before the UNFCCC conference in Copenhagen, where a new climate agreement was to be signed, Russia adopted the Climate Doctrine with very good scientific basis of the anthropogenic climate change [8]. Timely decisions are typical for the other BRICS countries, too.

Currently, a new agreement will be fundamentally different from the Kyoto Protocol in that all states will have to contribute to the global action, instead of only those that have the status of developed countries in the UN [17]. The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued in 2014 [6] outlines various options for collective action of all countries in the XXI century to limit the damage from climate change. There are several options for how the collective burden can be distributed between countries [15]. However, it is very difficult for the countries to “take the first step simultaneously and in the same manner”, i.e. to assume a “burden” beyond their direct economic interests with no guarantee of their partners acting the same way. In addition, the world largest economies and BRICS countries so far do not have a clear understanding of their future monetized economic losses from delays in emissions reduction. These losses, that are really huge, are already understood by a number of island states and the most vulnerable small countries, yet not by the largest economies [7, 9, 10].

This is why the “top-down” approach, i.e. from the global goal to the national action, is only being discussed in the UN, but not applied. Instead, a “bottom-up” approach is used: each country provides information on the contribution made (emissions reduction, reforestation, share of RES, technology transfer, adaptation measures, etc.) based on the national plans. Let us note here, that even the commitments made by countries under the new agreement were called “national determined contributions” in 2014 [17]. And the image is improved through aggressive propaganda of the given contributions taken on the national level. Therefore, the impact provided by UN-level international commitments on the national policies should probably be viewed as a factor of delayed effect that can only manifest in 10-15 years, after the largest countries have realized their losses from delayed action.

Participation in global emission trading

After the Kyoto Protocol was adopted in 1997, the impression was that international emissions trading would become a large-scale practice. While a number of options were explored, none were implemented [1, 18]. The US did not participate in the protocol. Japan purchased a relatively small amount of allowances to meet its commitments. Some East European countries sold their allowances. Russia did not take part at all. The volume of transactions was incommensurably smaller, than in the European Trading System, (ETS) which was the main internal system [18]. ETS was successful at the beginning, but it collapsed in crisis of 2008-2010 because it was not designed to work in stagnation or allowances surplus caused by a drop in production. While the EU is currently trying to restore the system, its joining with other national systems is delayed for a faraway future (except for Norway, Switzerland, etc., which does not make any difference).

However even, if ETS had succeeded, the global system would not have worked out. The reason is a change in the global GHG emissions structure. In the early- and mid-1990’s, when the Kyoto Protocol was being prepared, developed economies were responsible for the larger part of both emission volume and growth, whereas in developing countries just a small growth was observed. Today, on the contrary, developed countries are reducing their emissions, while developing states show fast growth and are approaching 70% of the global emission. China has left behind the U.S., India is ahead of Russia, and so on [4, 11].

Therefore an agreement should provide GHG reduction just in developing countries, at least the large ones. However, most of these countries lack resources for this purpose and have other priorities, e.g. economic development and alleviating poverty. The problem cannot be addressed, unless developed economies provide them with substantial funding earmarked for climate finance. Thus, a new agreement is needed to provide funding to the developing countries so they could reduce GHG emissions. This is not to replace emissions reduction by the developed economies, but is meant to make a huge difference by adding another “dimension” to 1D (quantifiable GHG volumes) process. Now the action would be at least “two-dimensional”: emissions and finance (and the finance is earmarked). It is in the philosophy of the new agreement, while the 2D (GHG and finance) process cannot be managed by emission trading [1, 17].

In addition the “bottom-up” approach makes emission trading baseless. Why make strong commitments taking the risk of incompliance (with allowance purchase) instead of taking weaker contributions? Why purchase allowances that neither facilitate technological development of your own economy nor promote your own business to the foreign markets? Isn’t it better to provide earmarked funding, for example, to finance projects of your companies in recipient countries or to address urgent social and environmental problems, e.g. clear-cutting of tropical rainforests, generating good image of donor-countries and its’ leaders?

It does not mean that emission trading will be excluded from the new agreement. It will be there, but only as a limited tool for a few donors, e.g. Norway highlighted willing to buy allowances through international market mechanisms.

Participation in international free market project-based mechanisms

Two such mechanisms were included in the Kyoto Protocol. The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) for projects in the developing countries and Joint Implementation (JI) for projects in the developed states. It is free-marked tools based on cost of GHG reduction (with limited national restrictions and taxes). Participation was the key factor for BRICS countries in 2009-2012. Russia had about 100 JI projects, and CDM had generated about 7000 projects, mainly in China, India and Brazil [1, 17]. Currently JI is hold, CDM projects are still being continued, but without chance for growth because ETS may accept only “old” CDM projects of 2008-2012, and nobody else of large potential buyers is going to accept CDM allowances, e.g. Japan created own Joint Carbon Mechanism (JCM).

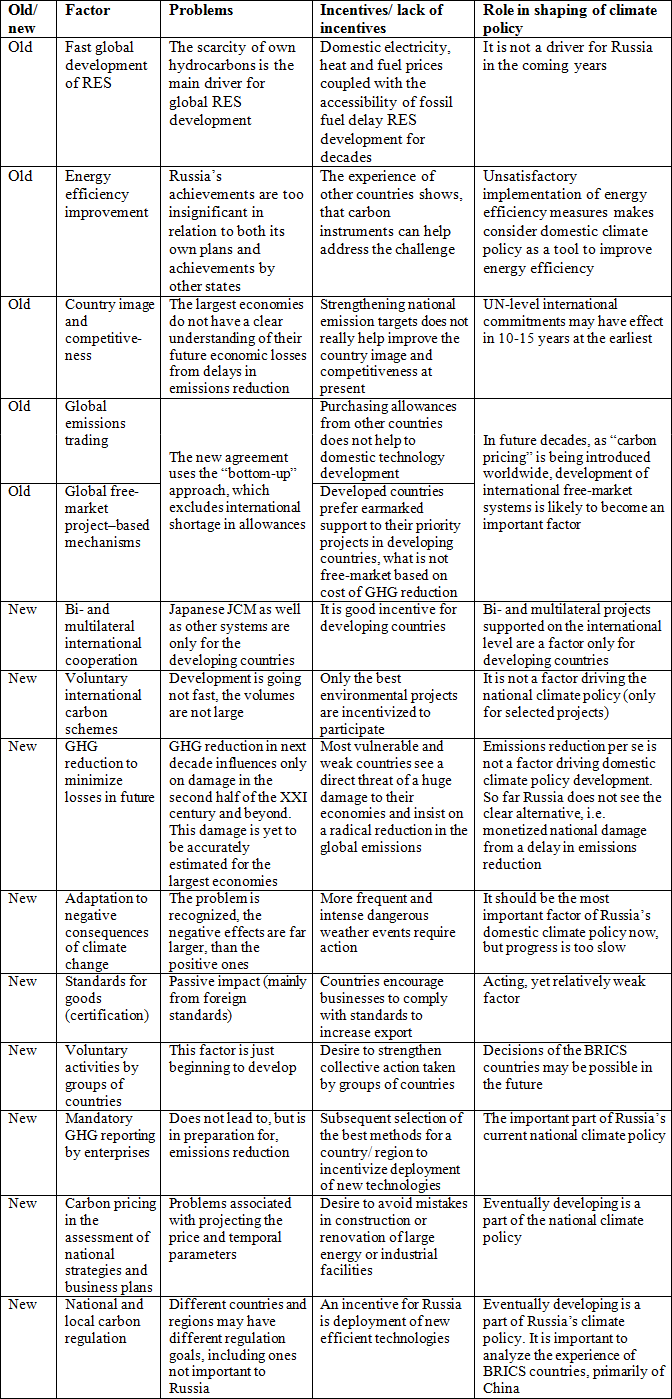

In the new agreement role of the project-based free-market mechanisms will be very small. The reasons are the same as for emission trading. Arguing as above such mechanisms probably will be in the agreement, but with minor priority. What we have now, is transformation of the global emissions trading and free-market allowances ideas into other ideas, e.g. bi- and multilateral cooperation, which is not free-market, but managed by priorities of partner-countries, see Table 1.

Table 1 - The role of old and new factors in shaping of climate policy

New factors driving climate policy development

Projects by bi- and multilateral international cooperation

To a certain extent, bi- and multilateral international cooperation is intended to replace CDM projects of the Kyoto Protocol. JCM, a Japanese initiative, is one example of such action slated for replication in dozens of developing countries [17]. It looks similar to CDM and differs in that there are no plans for reselling certified emissions reduction units, there is no free-market based on cost of GHG reduction. It is sort of earmarked support (purchase of the units by one buyer – Japan) with priority to facilitate development of Japanese business in other countries as well. Another example is German Climate initiative, which also considers specific projects on the bilateral basis and requires certified carbon “outcome”. Cooperation in combating elimination of tropical forests is one more example [17].

These schemes do not really have a role to play in Russia, as they are intended as an offset for the UN Official Development Assistance or for financing the activities in the developing countries only.

Voluntary international carbon schemes

These are being developed successfully, albeit not very fast [18]. Participation in these schemes can hardly be a factor driving Russia’s climate policy. On the one hand, the operation volumes are incommensurable with Russia’s need for technological re-equipment, and on the other, all deals require a lot of promotion for the projects, i.e. highlighting their social importance and aggressive propaganda in international media. These schemes are of course viable for the best environmental projects, but they are not important at the national level of a large country.

Reduction of damage from anthropogenic climate change

This factor is driven by risks and losses caused by delays in mitigation (it is mainly GHG emission reduction) and adaptation measures. The mitigation is principally global, while adaptation is mainly regional, national and local. The climate system includes ocean as the main element with very large inertia. Therefore any mitigation in the next 10-20 years influences only on damage in the second half of the XXI century and beyond. It is time horizon of mitigation. Negative consequences of climate changes in the next decades could be eliminated only by adaptation, while it will be required later on as well. On the other hand, any national adaptation cannot prevent large losses after the middle of the XXI century, if global mitigation is too weak [6, 15].

The UNFCC has adopted the goal to keep global temperature growth below 20C from preindustrial level by the end of the XXI century. However the Fifth IPCC Assessment Report shows that such fast mitigation is very difficult task. It is more likely that at 2100 the temperature growth will be 3-40C (currently it is 0.80C) with corresponding extreme events, sea level rise, risk of large-scale fresh water deficit, droughts and etc. [6]. Precautionary principle requires undertaking adaptation by +40C scenario. The UNFCCC has now new task to formulate Global Goal on Adaptation for the new agreement. More than 100 weakest and most vulnerable countries strengthened pressure on the largest economies [15, 17]. Now this pressure is driven not only by an intention to obtain funding, but also by the recognition of the climate problem per se.

Adaptation

Over the recent 15-20 years, in Russia dangerous extreme weather events have grown in number from 150-200 to about 400 per year [10]. Damage entailed by floods, heat waves, forest fires, droughts and other impacts by far outweighs any potentially positive effects, such as reduced space heating costs. Unlike ten years ago, there is a general understanding in Russia that climate change basically entails the negative effects, rather than benefits. Concerns over the adverse effects were quite correctly highlighted in the Russian Climate Doctrine. However, adaptation measures are just being launched in Russia, so adaptation is a new and very important national climate policy factor.

Mitigation

As it was highlighted in the above, reducing of the GHG emissions in 2010-2030 impacts only on the future climate changes. The indirectness affects policymakers and businessmen. There is also lack of reliable assessments of the monetized losses to the leading economies entailed by delays in mitigation (such assessments are available on global level and for most vulnerable countries) [6, 7, 9]. Indeed, for them it is much more difficult to assess the damage, particularly if caused not so much by a relatively well projected sea level rise or fresh water deficit, as by a far more uncertain increase in the number of extreme events (exactly the case for Russia) [6, 10]. Therefore, as fast as possible emissions reduction per se has not so far become the ultimate goal for Russia or other leading economies, despite the fact that the most vulnerable states are pressing hard for this in the UN.

Products / services certification

There are multiple certification (labeling) systems for products and services that are based on energy efficiency parameters which often translate into specific CO2 emissions as well. A certification system itself may aim at quite different goals. For example, Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification of logging activities primarily aims at environmental friendly logging that promotes faster reforestation, does not impair creeks or water bodies, does not entail slope erosion, etc. At the same time, FSC logging allows to prevent soil organic matter from decomposition and so to avoid CO2 atmospheric emissions. Many countries already refuse to import wood products, including paper, that are not FSC-certified. This fact has already incentivized Russian timber industrialists for FSC certification, and Russia currently ranks second (after Canada) among the world countries in having the largest FCS-certified forest area. This is a good example of synergy between the environmental protection and low-carbon goals.

Russia has to encourage its businesses to be compliant with such certifications, and so they are “automatically” included in the climate policy. However, like in the above example of FSC certification, this may be just a passive activity, i.e. Russia’s response to external certification “challenges” that have to be addressed in order to sustain the competitiveness of products.

Voluntary compliance with decisions made by a group of countries

What is meant here is voluntary compliance with a collective decision made by a group of countries, if membership in the group is of principal importance to a country, e.g. Russia. For example, the Arctic Council has decided to make national black carbon (solid particular matter absorbing solar radiation and consisting mostly of soot) emission inventories and submit corresponding reports. Albeit Russia has not yet accomplished much of the groundwork and does not have the technical ability required to submit such reporting, it decided to join other Arctic Council members and agreed to the development of voluntary inventories and submitting the first inventory report in 2016.

Russia’s participation in the collective action of the BRICS countries may strengthen its climate policy, because our BRICS partners often pursue more proactive climate policies, than we do. However in the framework of UNFCCC they are members of a special BASIC group, which holds regular meetings trying to closely coordinate its foreign climate policy. All of them are developing countries and members of the Group of 77 and China, which is mostly opposed to the developed economies under UNFCCC. Russia’s joining the BASIC is impossible, but joint efforts in BRICS may be quite possible in future.

Mandatory emissions reporting by enterprises

Mandatory reporting of GHG emissions by economic agents (enterprise- or company-level reporting) is becoming an increasingly common world practice. The BRICS countries are enforcing this type of reporting for large- and medium-size enterprises in various sectors of economy in order to have a clearer picture of the situation and possibilities for subsequent carbon regulation [5, 9, 13]. National level GHG emission reports submitted to the UNFCCC now, which are mandatory for all countries, do not provide such information.

Carbon pricing in national, company- and enterprise-level development plans

This implies carbon pricing for the assessment of national plans and business plans of individual projects, whether private or public. World Bank is advocating this activity [13], considering carbon pricing to be a necessary parameter of its future projects. However, this is not just about the World Bank projects. The goal is far larger and includes giving an advance warning signal to the national and international businesses. Long-term projects, for example dealing with the energy sector development, should not “unexpectedly” turn out cost-ineffective in 20 or 30 years because GHG payments may become due, although not accounted for at the initial stage. It is difficult to say, of course, when and which payments will be required; only a scenario-based projection can be provided. However, it is very important to get the message across to the business circles and to allow for the corresponding options in long-term national energy and economic development strategies. This issue is currently discussed in Russia, too [2, 5, 9].

National and local action

The “bottom-up” approach to the development of the new global agreement and determined thereby lack of a trend for fast development of a global emissions trading system promoted the launch of national and local (subnational) carbon regulation systems [5, 6, 13]. The global experience shows, that commercialization of new technologies is a slow process, and so governments provide certain incentives. These incentives are not limited to administrative and regulatory measures alone.

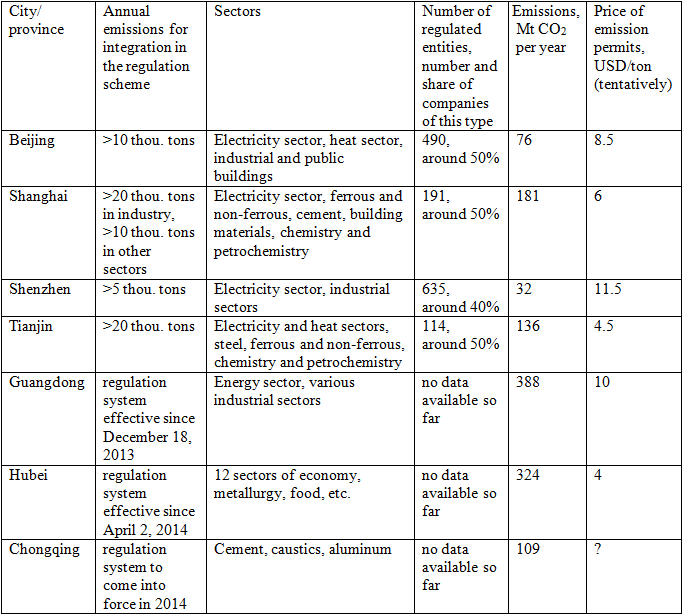

China is already using, and Brazil and South Africa are about to use, carbon instruments to incentivize the deployment of new technologies. India and Russia, have decided to carefully look into the problem [5]. China’s experience seems the most valuable for Russia. Firstly, it is a practical experience of accelerating the technology re-equipment, while a number of other countries aimed at other goals, such as energy independence of the EU, creating jobs in the U.S. states, etc. At the initial stage, the main purpose in China was to reduce air pollution in cities through closing down small coal-fired power plants; but now the scope has expanded and is transforming towards the technology re-equipment (see Table 2). Secondly, it is an experience of pilot action taken both in industrial and less developed regions to test the regulation schemes for various sectors. Carbon pricing shifts technology priorities towards more energy efficient solutions. At the same time, using trading schemes and flexible issuance of permits allow to find soft solutions for the businesses.

Table 2 - China’s approach to practical carbon regulation

Source: based on data from [13].

Summary of factors for Russia’s climate policy development

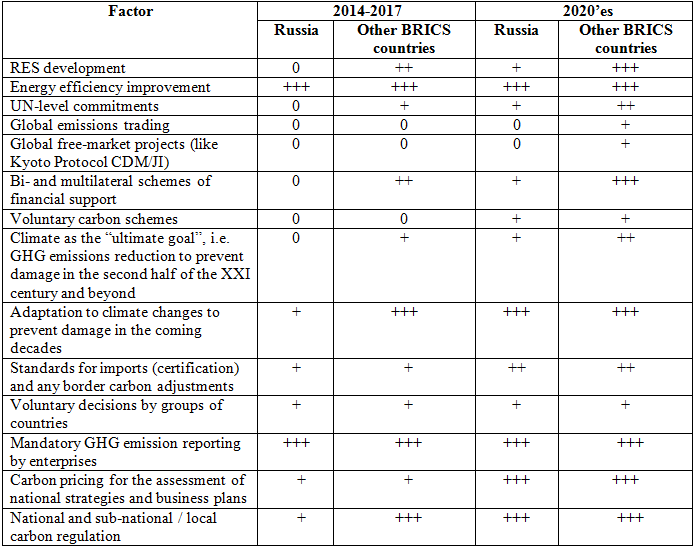

This summary provides a brief description of the above considerations, see Table 3. Like for the other BRICS countries, energy efficiency and substantively technological re-equipment of the economy is a top priority for Russia. Energy efficiency will maintain its role as the leading factor in the future, too. Another common factor is a trend for introducing enterprise-level reporting to be followed by some kind of carbon regulation depending on the goals. The goals diversity is well illustrated by the above evidence from China.

Table 3 - Estimated current and potential role of the old and new factors driving climate policy

Effects on the climate policy

0 – no + - weak ++ - moderate +++ - fundamental

On the other hand, Russia will for a long time be lagging behind the other BRICS countries in two factors: the first one is RES development [2, 3, 16], and the second factor is bi- and multilateral financial support schemes that are likely to be actively used by such countries as India, Brazil, and South Africa under the new global UN agreement, whereas Russia cannot be recipient of financial support by the given schemes [17]. It is likely, too, that Russia will be lagging behind in the climate mitigation factor, i.e. in the GHG emissions reduction to prevent damage in the second half of the XXI century and beyond. Russia is relatively invulnerable to the sea level rise, which is the best assessed damage at this point. Russia is also less vulnerable to droughts, than the other BRICS countries: before the end of the XXI century water deficit may be expected only in the southern Russian regions [6, 10].

However the overall finding is that Russia is going by the same road in the climate policy development, as the BRICS countries as a whole. Many factors could work in Russia as well as in the other BRICS countries, Tab. 3. The lag can be roughly assessed as 5-10 years and it is likely to see shrinking with time: many of the necessary preconditions are in place. In particular there is a delay in taking adaptation measures, but the government, business circles and the population are putting more focus to the problem, and the lag will be getting smaller. The catching-up problem is not to be treated mechanistically, and in the coming years priority should be given to the carbon reporting/regulation and adaptation measures.

This article was accomplished as part of cooperation between WWF-Russia and the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration under the project “Analysis of long-term energy efficiency scenarios for Russia using RU-TIMES optimization model”.

References

- Agibalov S., Kokorin A. Copenhagen Agreement – a new paradigm of climate problem solving [Kopengagenskoe soglashenie – novaya paradigma resheniya klimaticheskoy problemy] // Voprosy Ekonomiki – Economic Issues. - 2010. – No 9.- pp. 115-132. (in Russian).

- Bashmakov I.A. Expenses and benefits of low carbon economy and transformation of society in Russia. Perspectives by 2050 and beyond [Zatraty i vygody nizkouglerodnoi ekonomoki i transformatsii obschestva v Rossii. Perspektivy do i posle 2050 g.]. M.: CENEf, 2014. 178 p. Available at: http://www.cenef.ru/file/CB-LCE-2014-rus.pdf (in Russian).

- Global and Russian Energy Outlook Prognosis. M.: ERIRAS, REA, 2012. 196 p. Available at: http://www.eriras.ru/data/94/eng

- IEA Statistics. Key World Energy Statistics. Paris. International Energy Agency, 2014. 82 p. Available at: iea.org

- Implementation of the Decree of the RF President No 752 “On greenhouse gas emission reduction”. Decision of the Russian Federation Government [Vo ispolnenie Ukaza Presidenta RF No 752 “O sokraschenii vybrosov parnikovykh gazov”. Rasporyazhenie Pravitelstva Rossiiskoi Federatsii] 02.04.2014. No 504-p. Available at: http://www.garant.ru/products/ipo/prime/doc/70530682/ (in Russian).

- IPCC Fifth Assessment Report, Climate Change 2013–2014. Cambridge University Press. 2013–2014. vol. 1–3. Available at: ipcc.ch

- Kokorin A.O., Gritsevich I.G., Gordeev D.S. Greenhouse Gas Emission Scenarios for Russia and Rest of the World // Review of Business and Economic Studies (ROBES). - 2013. - vol.1, issue 1, pp.55-66. Available at: http://www.fa.ru/projects/rbes/about/Pages/default.aspx

- Kokorin А.О., Korppoo A. Russia’s Post-Kyoto Climate Policy Real Action or Merely Window-Dressing? // FNI Climate Policy Perspectives. - 2013. – No 10. – 8 p. Available at: fni.no or www.perspectives.cc

- Kokorin A., Korppoo A. Russia’s greenhouse gas target 2020: Projections, trends and risks. (F. E. Foundation, Ed.) Study. Berlin: Friedrich Ebert Foundation. - 2014. – 18 p. Available at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id-moe/10632.pdf

- National report on climate features on the territory of the Russian Federation for the year 2013 [Natsionalnyi doklad ob osobennostyakh klimata na territorii Rossiiskoi Federatsii za 2013 god]. M.: Roshydromet, 2014. 110 p. Available at: meteorf.ru

- Oliver J.G.J., Janssens-Maenhout G., Muntean M. and Peters J.A.H.W. Trends in global CO2 emissions; 2013 Report. The Hague: PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency; Ispra: Joint Research Centre, 2013. 64 p. Available at: pbl.nl/en

- Russian Statistics [Rossiiskaya statistika] // Energeticheskii Bulleten, Analyticheskii Centr pri Pravitelstve RF- Energy Bulletin of the Analytical Center of the RF Government. – 2014. – No 17. – 32 pp. Available at: http://ac.gov.ru/publications/ (in Russian)

- State and Trends of Carbon Pricing. Washington, DC: World Bank. 2014. 135 pp. Available at: carbonfinance.org

- State Program “Energy efficiency and energy development” [Gosudarstvennaya programma “Energoeffektivnost i razvitie energetiki”]. M.: Ministry of Energy of the Russian Federation, 2014. 84 pp. Available at: http://www.energy.gov.ru/documents/razrabotka/17992.html?sphrase_id=851278 (in Russian)

- The Emissions Gap Report 2012. UNEP Synthesis Report. Nairobi: UNEP, 2012. 62 pp. Available at: http://www.unep.org/publications/ebooks/emissionsgap2012

- The Pathways to Deep Decarbonization. Paris: Sustainable Development and International Relations, 2014. 232 pp. Available at: deepdecarbonization.org

- United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change. Official information, documents, submission of the Parties [Electronic resource] URL: unfccc.int (date of publication 24.11.2014)

- Yulkin M.A., Dyachkov V.A., Samorodov A.V., Kokorin A.O. Voluntary systems and standards of greenhouse gas emission reduction [Dobrovolnye sistemy i standarty snizheniya vybrosov parnikovykh gazov]. : Vsemirnyi fond dikoi prirody (WWF), 2013. 95 pp. Available at: http://www.wwf.ru/resources/publ/book/799 (in Russian)