АНТРОПОМОРФИЧЕСКИЙ ХАРАКТЕР МЕТАФОРИЧЕСКИХ МОДЕЛЕЙ ПЕРСОНИФИКАЦИИ В РОМАНАХ Т. ПРАТЧЕТТА

Юрина Н.М.1

1Аспирант, Башкирский государственный университет

АНТРОПОМОРФИЧЕСКИЙ ХАРАКТЕР МЕТАФОРИЧЕСКИХ МОДЕЛЕЙ ПЕРСОНИФИКАЦИИ В РОМАНАХ Т. ПРАТЧЕТТА

Аннотация

В статье рассмотрено использование антропоморфизма для построения метафорических моделей персонификации на примере цикла романов Т. Пратчетта «Плоский мир», и, соответственно, создания художественных образов.

Ключевые слова: персонификация, метафорическая модель, фрейм, слот.

Yurina N.M.1

1Postgraduate student, Bashkir State University

ANTHROPOMORPHIC CHARACTER OF METAPHORICAL MODELS OF PERSONIFICATION IN NOVELS BY T. PRATCHETT

Abstract

The article consideres the use of anthropomorphism to establish the metaphorical models of personification in T. Pratchett’s “Discworld” series, and, its use for the image creation.

Keywords: personification, metaphorical model, frame, slot.

The analysis of the nature of personification as an instrument of creating expressive means of language reveals that it is a peculiar and many-facet unit possessing a number of features and a set of language means allowing different degrees of its intensity. The notion covers a certain variety of senses ranging from animation to humanization, that is why the area of personified objects in literature and everyday communication is vast and this concept spreads over virtually all phenomena and notions of the world around us. However, the only area all linguists agree upon is that the phenomenon is based on the category of animacy/inanimacy, which leads to a series of terms and notions: metaphor, allegory, personification, personalization, prosopopoeia, anthropomorphism, zoomorphism, animism.

Despite a great number of possible synonyms or types of the phenomena described, I am inclined to follow the idea of such linguists as N.M. Naer, A.S. Lebedevsky, W. Wackernagel, O.S. Akhmanova and hold to the term personification, which in this work is understood as a “stylistic device, a special type of metaphor, involving the transfer of attributes and properties of a human being or an animal (such as consciousness, an ability to think and feel, and a speech power) to an inanimate or abstract object, devoid of human consciousness” [8, 57-58]. Since personification is a type of metaphor, its use and manifestation in the text is realised in cognitive models, which makes it possible to analyse this process in terms of metaphorical models analysis in literary discourse [8].

The study of the metaphorical models of personification in T. Pratchett’s novels has shown that the prevailing mechanism of their creation is anthropomorphism, i.e. attributing human characteristics to lifeless objects [8]. Consequently, it deserves a detailed research of its own. Having studied the use of this phenomenon in the novels of the Discworld series, it is possible to single out two major frames in the group of anthropomorphic models of personification:

- Frame “Human Being”

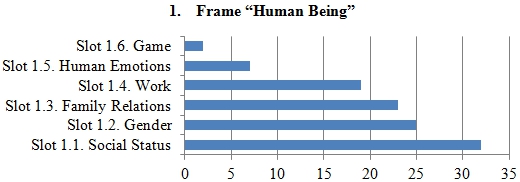

The majority of scholars agree that common nouns in the English language do not possess the category of gender and the sex is shown only due to the lexical meaning of the word (e.g. boy or girl), thus usually only people are treated as being male or female, that is why one of the key signs of personification is the use of such lexical units as pronouns he or she with common nouns. However, not all cases of T. Pratchett’s personification share this feature. Unlike most minor personified characters in T. Pratchett’s novels major characters have some gender indications that allow to single out such slots as man and woman; but, cases of personification of an object or abstract notion as a woman are too insubstantial and only include female gods. Thus, the frame “Human Being” covers 6 slots, the proportional correlation of which is shown on the diagram (figure 1):

Fig. 1

- Slot 1.1. Social Status

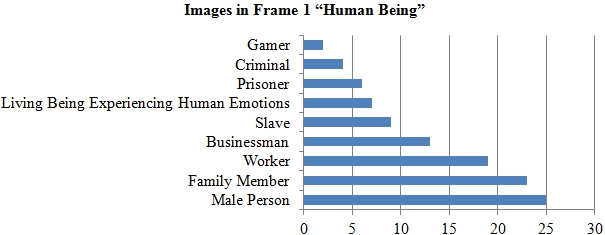

The attitude of T. Pratchett towards technology is very creative. Apart from the expected personification of various devices (robots, computers, office equipment, etc.), for example, in the story “The Computer Who Believed in Santa”, there is a very curious metaphorical model of personification when such devices as watches (or “time-tellers”) or cameras (or “iconography”) are transformed into magical boxes that are inhabited by enslaved or imprisoned demons instead of mechanisms: e.g. “the picture imp … had spent the morning painting picturesque views and quaint scenes for his master, and had been allowed to knock off for a smoke”; “Its trapdoor was open and the homunculus was leaning against the frame, smoking a pipe…” [4]. The idea of demons or other magical creatures imprisoned inside different devices to make them work forms another metaphorical image: a slave.

A very interesting and original case of personification is the personification of books. There are two types of such books: the books that write people’s lives and magic books. They have power and ability to affect or even destroy people or their surroundings, that is why, they are locked, chained, imprisoned, clumped shut unless they go out of control or escape, e.g. “Cutwell had an expurgated edition, with some of the more distressing pages clamped shut (although on quiet nights he could hear the imprisoned words scritching irritably inside their prison)” [6]. This gives rise to one more metaphorical image: a prisoner.

The image of a prisoner is somewhat interconnected with the one of a criminal. Although, comparisons of different characters with criminals are relatively rare. However, Death is always a witness, he watches everyone die or being killed. But sometimes he is perceived as an accessory or even the assassin: e.g. “as I understand the law, you are an Accessory After The Fact” [4];“I WAS THE ASSASSIN AGAINST WHOM NO LOCK WOULD HOLD” [5].

- Slot 1.2. Gender

In many languages (including English), Death is personified in a male form, while in others, it is perceived as a female character (for instance, in Slavic and Romance languages) [1]. T. Pratchett follows the custom and portrays Death as a man. Another such example concerns Fate. The common abstract noun is capitalised and becomes both the name and the essence of the god of a power that some people believe controls everything that happens in their lives. The description of a human appearance and the character are clear examples of personification of fate as a person and, more precisely, as a man: e.g. “the Fate of the Discworld was currently a kindly man in late middle age, graying hair brushed neatly around features” [3]. Thus, the prevailing image here is a male person.

- Slot 1.3. Family Relations

Another very important concept within the metaphorical model X is Person is that personified objects or notions have families. The notion of a family for some magical creatures or the representation of an abstract notion as a part of a family is a very important slot for metaphorical models of personification with the source domain “person” because even though animals also live in groups that resemble families (herds, prides, etc.), the relations that exist in a human family are entirely different. For instance, trolls that traditionally are treated as solitary, lonely creatures are shown as a big family that closely resembles a typical human family where the spouses are arguing about the place they live in, and the future of their children: e.g. “I just want to call the family up, all right? ... but I tell her, this bridge has been in our family for generations ...”; “I should have listened to my mother! You want me to let our son sit under a bridge waiting …” [7].

Another group of metaphors within this slot deals with associating particular characters with some positions in the family that have a particular status: e.g. “Death stalked around the desk … AND THUS YOU REPAY ME. YOU SEDUCE MY DAUGHTER FROM ME, YOU NEGLECT THE DUTY” [5]. In these examples Death is treated as the head of family, as a father. Such kind of personification is very unusual since death in general is associated with an unbiased impartial lonely creature, the sole purpose of which is to send the souls into the afterlife. Consequently, the major image behind these models is a family member.

- Slot 1.4. Work

The concept “job” is the third most common for the model X is Person. The impact of such abstract phenomena, such as time, death, etc. is the result of the work of these personified phenomena. The most frequent is the metaphorical use of lexis denoting the hard work, and the references to the fact that these characters have a job to do: e.g. “Time passed, which, basically, is its job” [3]. Here the normal course of time, its passage is viewed as a job that is done by Time.

The slot deals also with the idea of ranking and difference in the status between some characters in the novels. The lexical units include the names of positions (superior, subordinate, apprentice, master, servant, etc): e.g. “when a wizard is about to die Death himself turns up to claim him (instead of delegating the task to a subordinate, such as Disease or Famine, as is usually the case)”; “instead of sending one of his numerous servants, as is usually the case” [6]. Death is in charge, and sometimes he can assign the task to his subordinates or even his apprentice (Mort).

One more notion within this slot is business because not all metaphorical models with the source domain “job” include the concept of running a business. Some examples include the description of the persevering character of nature that gradually and determinedly achieves its aims: e.g. “every representative of the vegetable kingdom had really rolled up its bark and got down to the strenuous business of outgrowing all competitors” [3].

Other cases concern Death’s work. Death is a businessman, he has appointments, and his own system of doing business: e.g. “I HAVE AN APPOINTMENT WITH THEE THIS VERY NIGHT … WHAT’S SO BLOODY VEXING ABOUT THE WHOLE BUSINESS IS THAT I WAS EXPECTING TO MEET THEE IN PSEPHOPOLOLIS. “But that’s five hundred miles away!” ... THE WHOLE SYSTEM’S GOT SCREWED UP AGAIN” [4].

Thus, it is possible to single out two metaphorical images within this slot: a worker and a businessman.

- Slot 1.5. Human Emotions

Sometimes personification is manifested through such lexical units that the object possesses features of a living being, i.e. the mind, and, especially, emotions. The most prominent and frequently described example for this slot is Death who like any person is capable of feelings. Perhaps not feelings per se: e.g. “He never feels anything. ... He probably thought sorry for me.”, but still he shows some kind of emotions: “THEY NEVER INVITE ME TO PARTIES. THEY ALL HATE ME. EVERYONE HATES ME. I DON’T HAVE A SINGLE FRIEND [5]. Death is always alone, because he is on the opposite side from the living, he does not know what it means to be alive: “It struck Mort with sudden, terrible poignancy that Death must be the loneliest creature in the universe. In the great party of Creation, he was always in the kitchen” [5].

The personification of Death is a reversal of the human curiosity and preoccupation with the unknown. It is beyond the human abilities to know what lies beyond the grave. Likewise, Death himself cannot grasp the full meaning of life before the grave; however, he wants to discover what gives meaning to people's lives: e.g. “He’d tried fishing, dancing, gambling and drink, allegedly four of life’s greatest pleasures ... Food he was happy with—Death liked a good meal as much as anyone else”; “Death was bewildered. He couldn’t fight it. He was actually feeling glad to be alive, and very reluctant to be Death” [5].

- Slot 1.6. Game

The smallest slot is represented by a number of very interesting metaphors. The numerous gods are personified in the form of people who are playing dice and the stakes are human souls. As a result of this game, people’s fate is decided. e.g. “You win,” said Fate, pushing the heap of souls across the gaming table. The assembled gods relaxed. “There will be other games,” he added. The Lady smiled into two eyes that were like holes in the universe” [6].

The diagram (figure 2) sums up the major images created by this model of personification and their percentage correlation.

2. Frame “Intelligent Creature”

2. Frame “Intelligent Creature”

Sometimes the metaphorical model is so vague that it is not possible to include a character into any of the other frames given here. Nevertheless, the properties that are portrayed in these metaphorical models are clearly human since, for example, intelligence is associated uniquely with the human race. The concepts typical for this frame are expressed primarily through verbs, and adjectives that usually refer to human activities, such as to speak, to think, to talk, etc: e.g. “all colonies of bees are just one part of the creature called the Swarm, … bees are component cells of the hivemind. Granny … suspected that the Swarm was a good deal more intelligent than she was” [2]. In this metaphorical model Bees are Creature (the Swarm) such language units as mind, intelligent signify that the character possesses the qualities that are enough to attribute it to this frame.

A majority of other similar cases includes animals, parts of furniture (doorknobs, hinges, etc.), weapons (e.g. a sword) that behave like human beings: they speak, think and even give advice to their masters: e.g. “Fanks very much,” said the gargoyle doorknocker … The knocker leered at him and winked” [5].

Thus, it is clear that anthropomorphic personification is the most extensive and detailed. Although, cases of pure anthropomorphic personification, when the object or phenomenon is fully endowed with human properties, are not predominant; there is no doubt that other cases can also be treated as anthropomorphic personification due to the fact that the features they possess can only be attributed to human beings but not animals or plants, such as reasoning, consciousness, speech, feelings or emotions.

References

- Guthke K.S. The Gender of Death. A Cultural History In Art and Literature. – Cambridge University Press. – 1999. – 297p.

- Pratchett T. Equal Rites. – Victor Gollancz Ltd. – 1987. – 336p.

- Pratchett T. Faust – Victor Gollancz Ltd. – 1990. – 160p.

- Pratchett T. Guards! Guards! – Victor Gollancz Ltd. – 1989. – 384p.

- Pratchett T. Mort. – Corgi Books. – 2012. – 320p.

- Pratchett T. The Colour of Magic. – Colin Smythe Ltd. – 1983. – 206p.

- Pratchett T. Troll Bridge // A Blink of the Screen: Collected Short Fiction. – Corgi Books. – 2013. – pp. 217 – 235.

- Yurina N. The Metaphorical Models of Personification in novels by T. Pratchett // News of Science and Education 9 (9), 2014. – Science and Education Ltd, Sheffield, UK. – p. 57 – 60.